Drawing Pain: The Disappearance of Aisha Rashid and Other Middle Eastern Girls

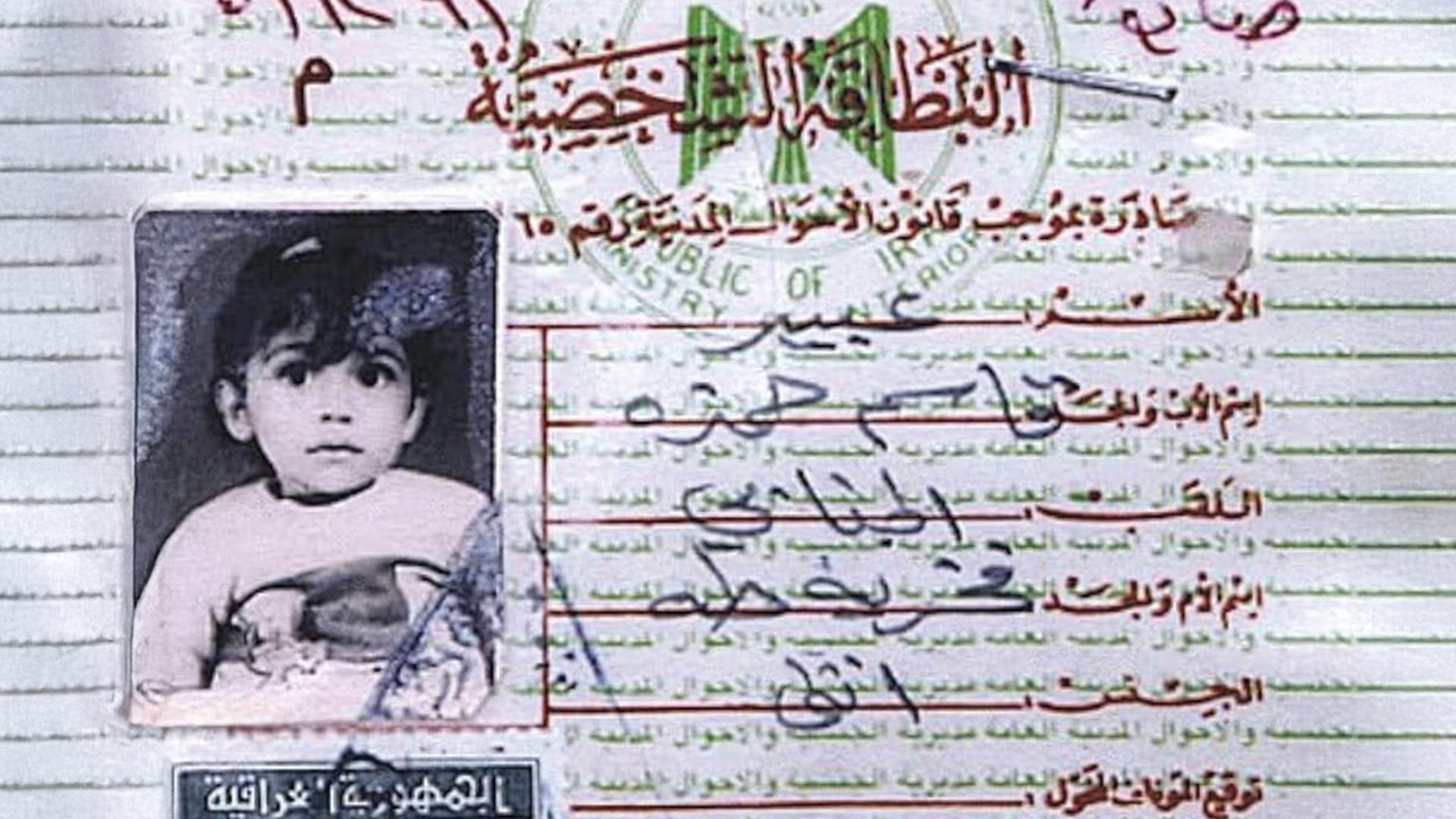

Seven year old Abeer Qassim al-Janabi,

seven years before her murder.

Seven year old Abeer Qassim al-Janabi, seven years before her murder.

Jump directly to specific sections of this article

using the links below.

Article Read Time

30 min

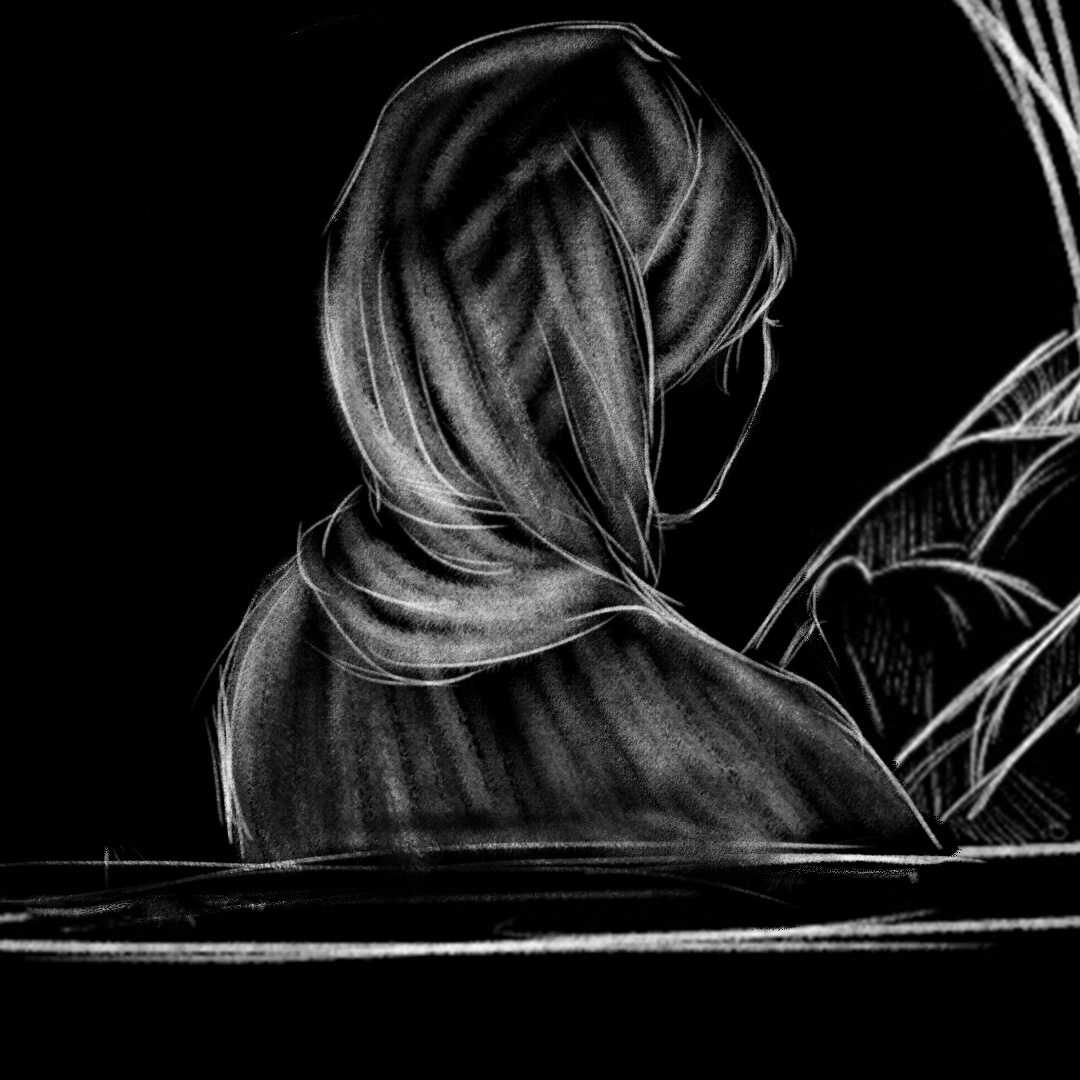

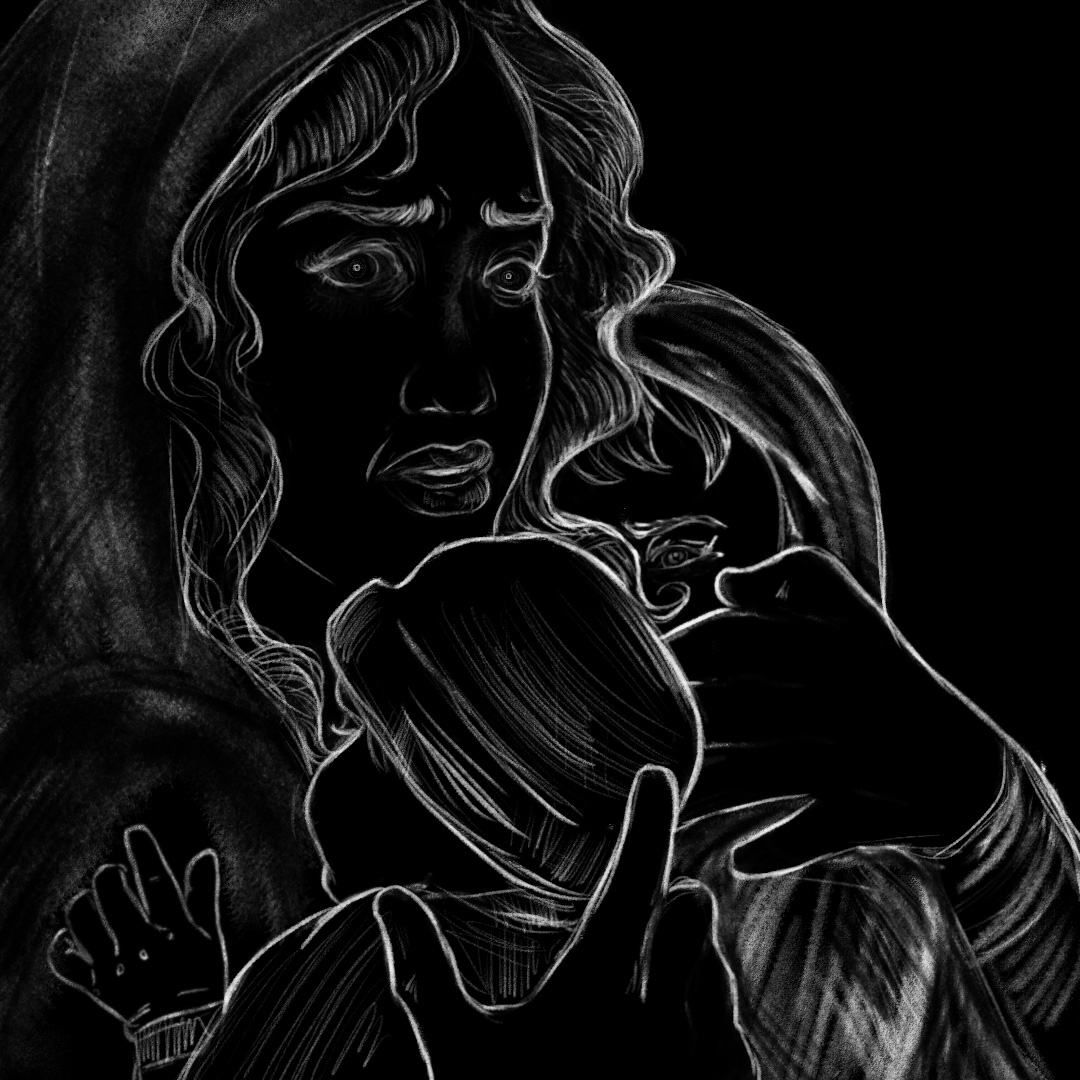

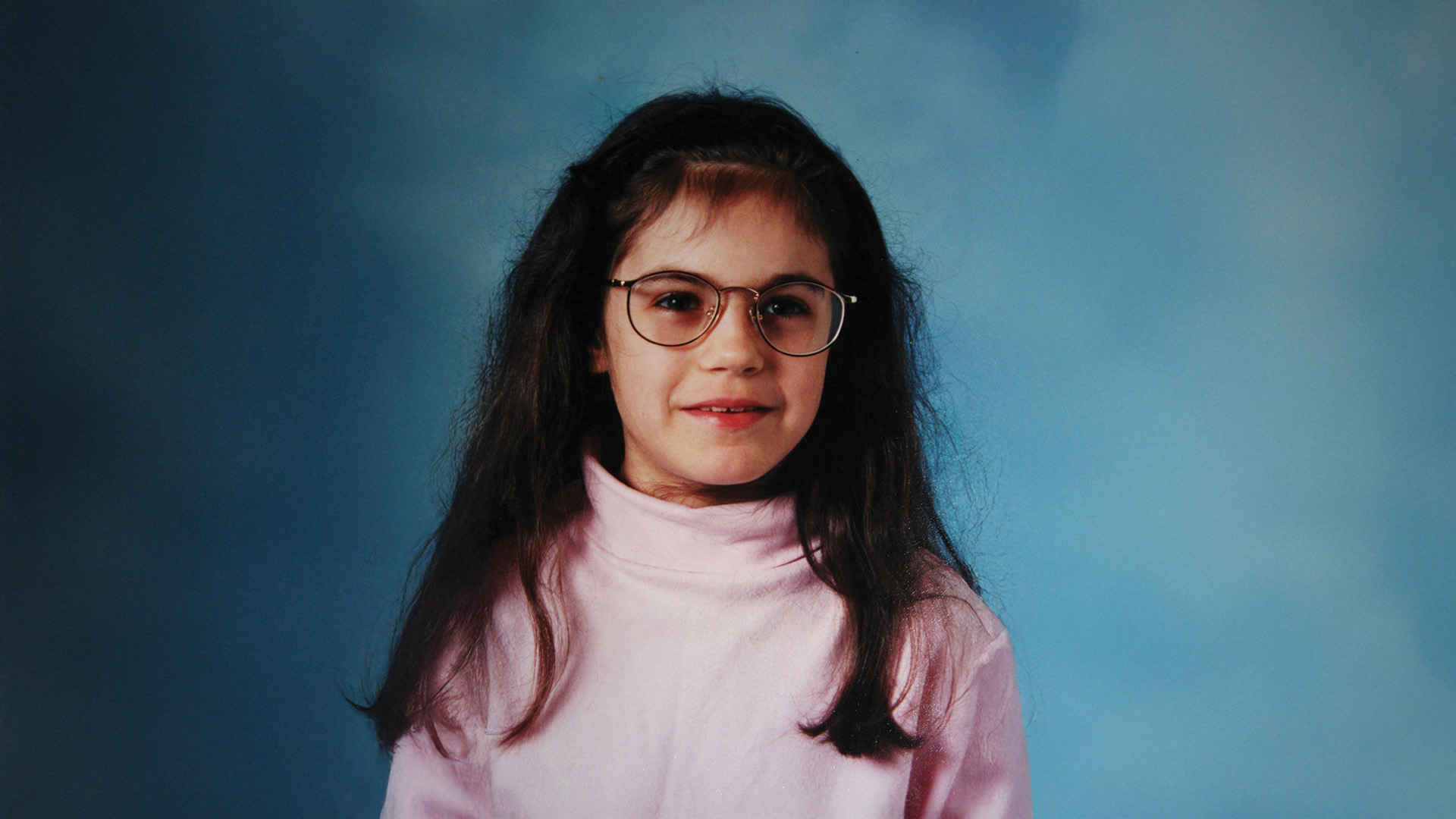

The author at seven years old.

Photo: School Picture Day, 1995

A Week After 9/11

A week after 9/11, my foreign language teacher took me and two other Iranian American girls aside after class.

An Iranian immigrant herself, she told us she was worried. Things would be dangerous now for people like us. Normally poised, her long-lashed eyes were afraid. Even though all three of us stood silently in front of her desk, something in my face must have prompted her next comment. She turned to me and said, reassuringly, that I would be fine since I didn’t look Iranian.

She wasn’t wrong. There are three things I didn’t inherit from my father: his math skills, his ability to speak Farsi, and his coloring. Though I sound and behave like him, my complexion comes from my all-American auburn-haired mother.

I was thirteen in 2001. I am thirty-seven now, in 2025. Whenever I think about that memory, I lose myself in the details: the little bowl of Ferrero chocolates she gave her best students, her perfect eyeliner, the shine of the other girls’ jet-black curls so unlike my bushy reddish-brown hair. Every time, I wonder how they felt hearing that, why they weren’t safe but I was.

It’s easy to dismiss that moment as a minor exchange in the aftermath of a major tragedy, but these everyday negotiations of safety and identity have shaped Middle Eastern communities ever since. They defined whose fears were acknowledged, whose security was prioritized, and whose lives were treated as expendable.

In the years that followed, it became even clearer that safety was never equally distributed. Entire regions were subjected to military campaigns framed as precise and humane. The real cost was measured in civilian lives, many of them children. Their deaths were explained away as mistakes or necessary collateral. Some survived with lifelong injuries. Others were targeted directly. Many more were swallowed by the machinery of violence in their own countries.

Each of these sacrificial lambs disappear – first from headlines, then from the first page of Google, and eventually altogether.

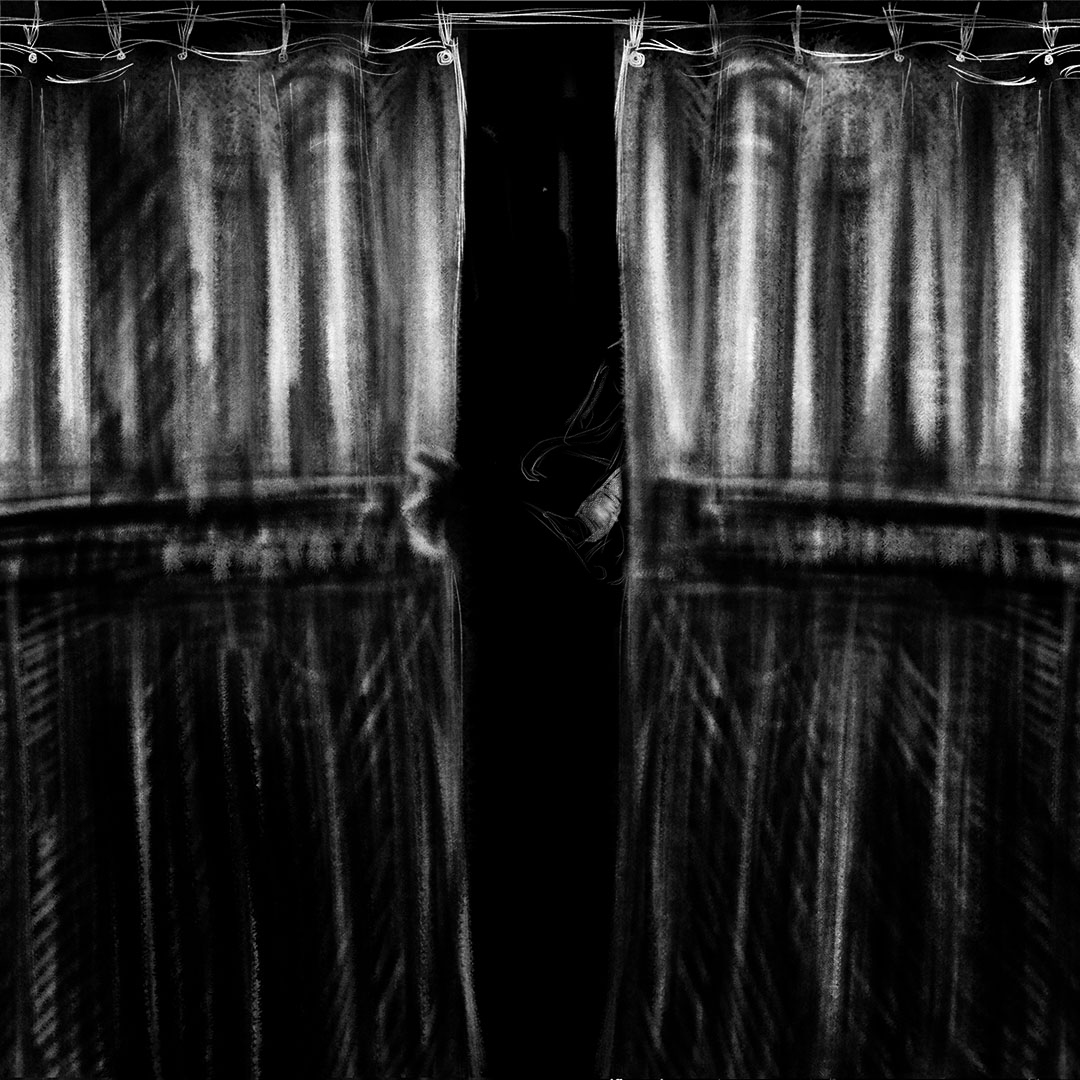

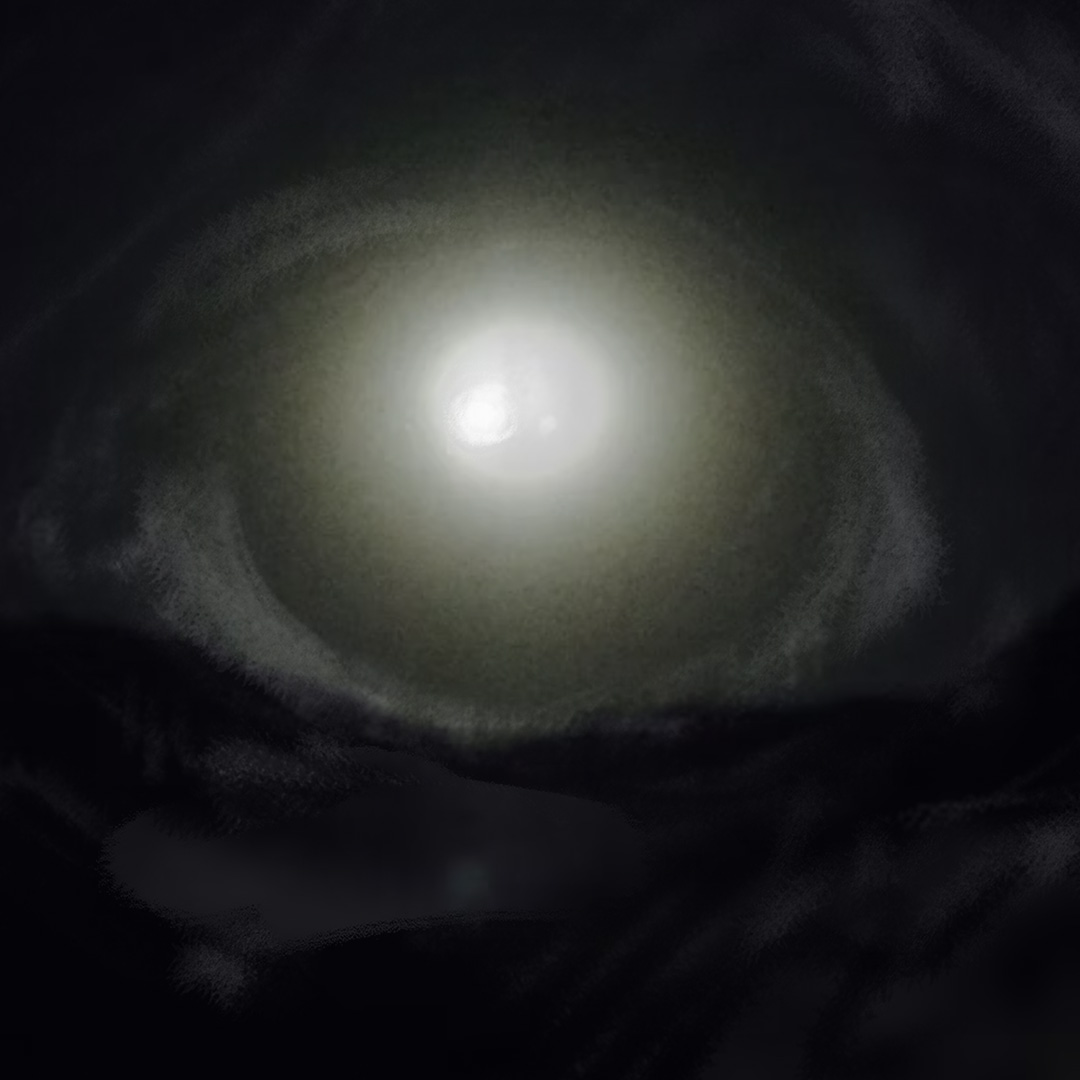

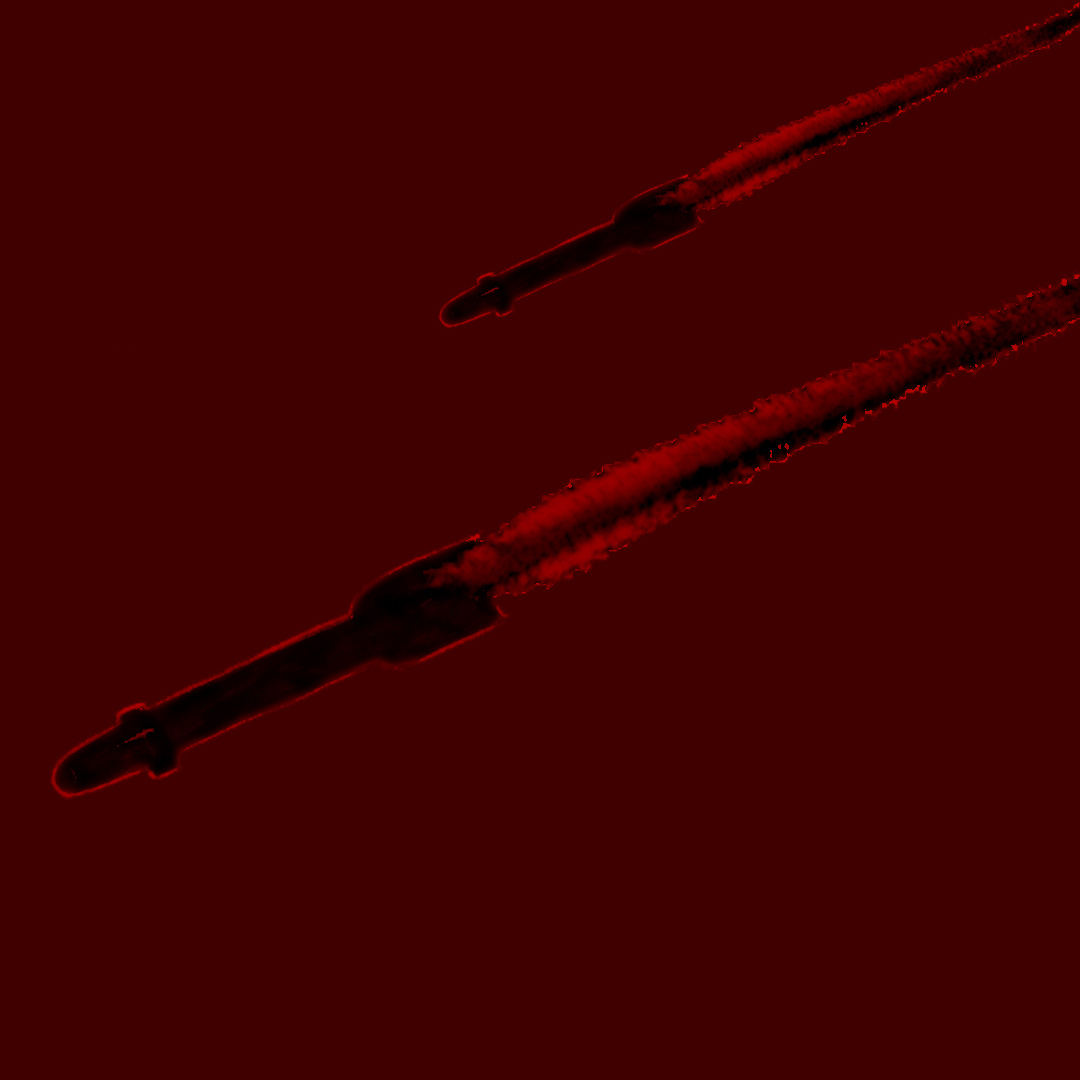

The truck in which Aisha Rashid and her family were traveling when it was destroyed by a drone strike in Afghanistan.

Photo: May Jeong, 2013

Aisha Rashid

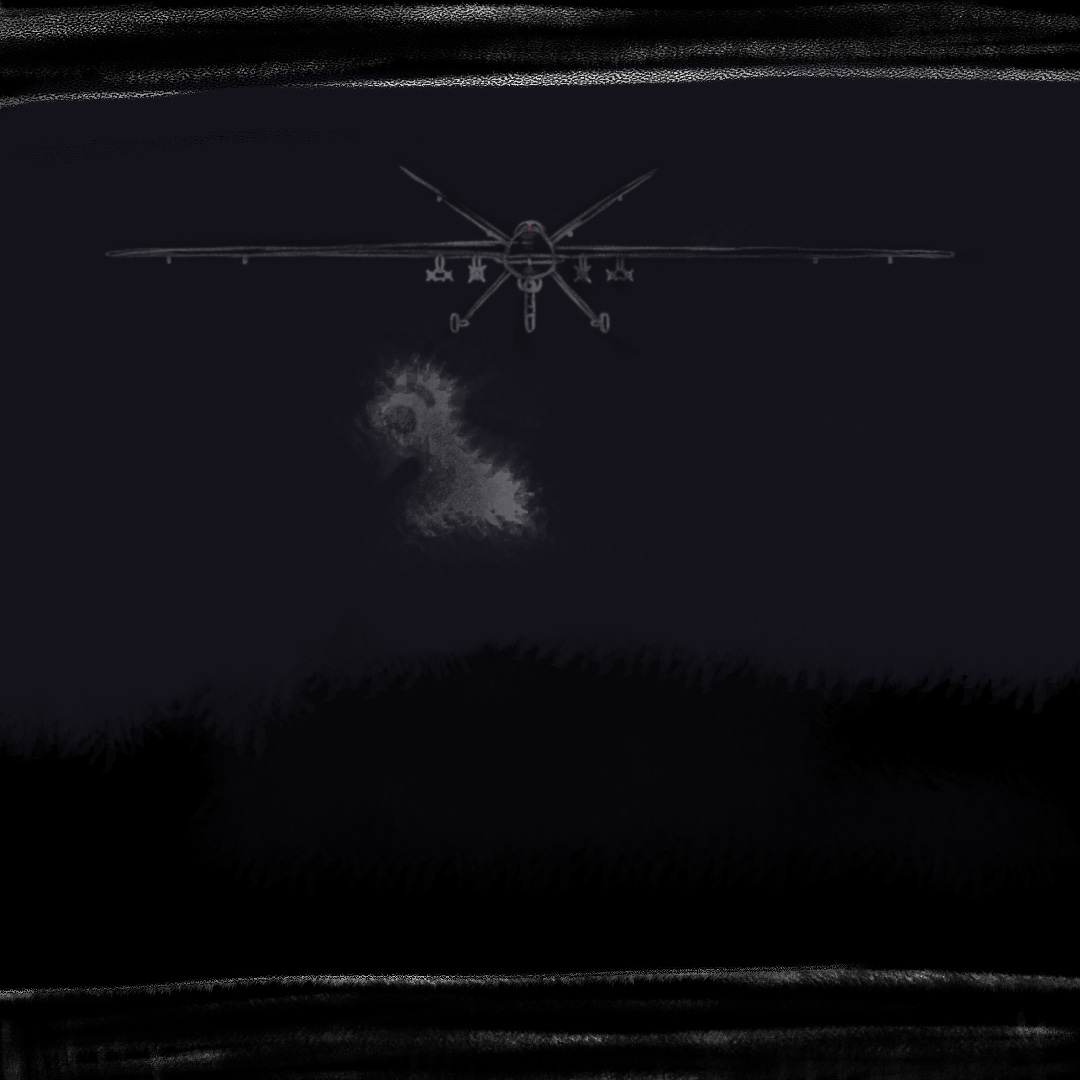

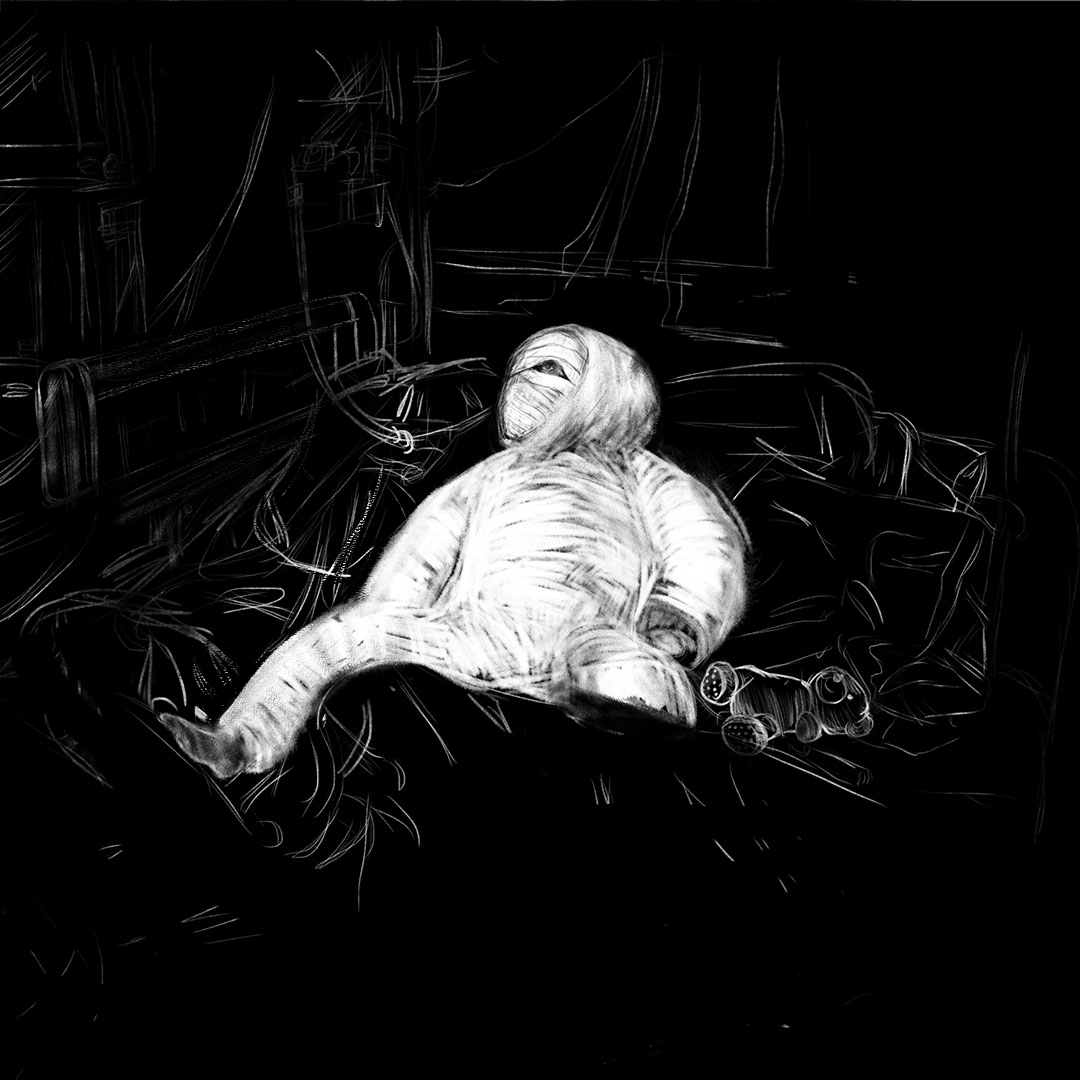

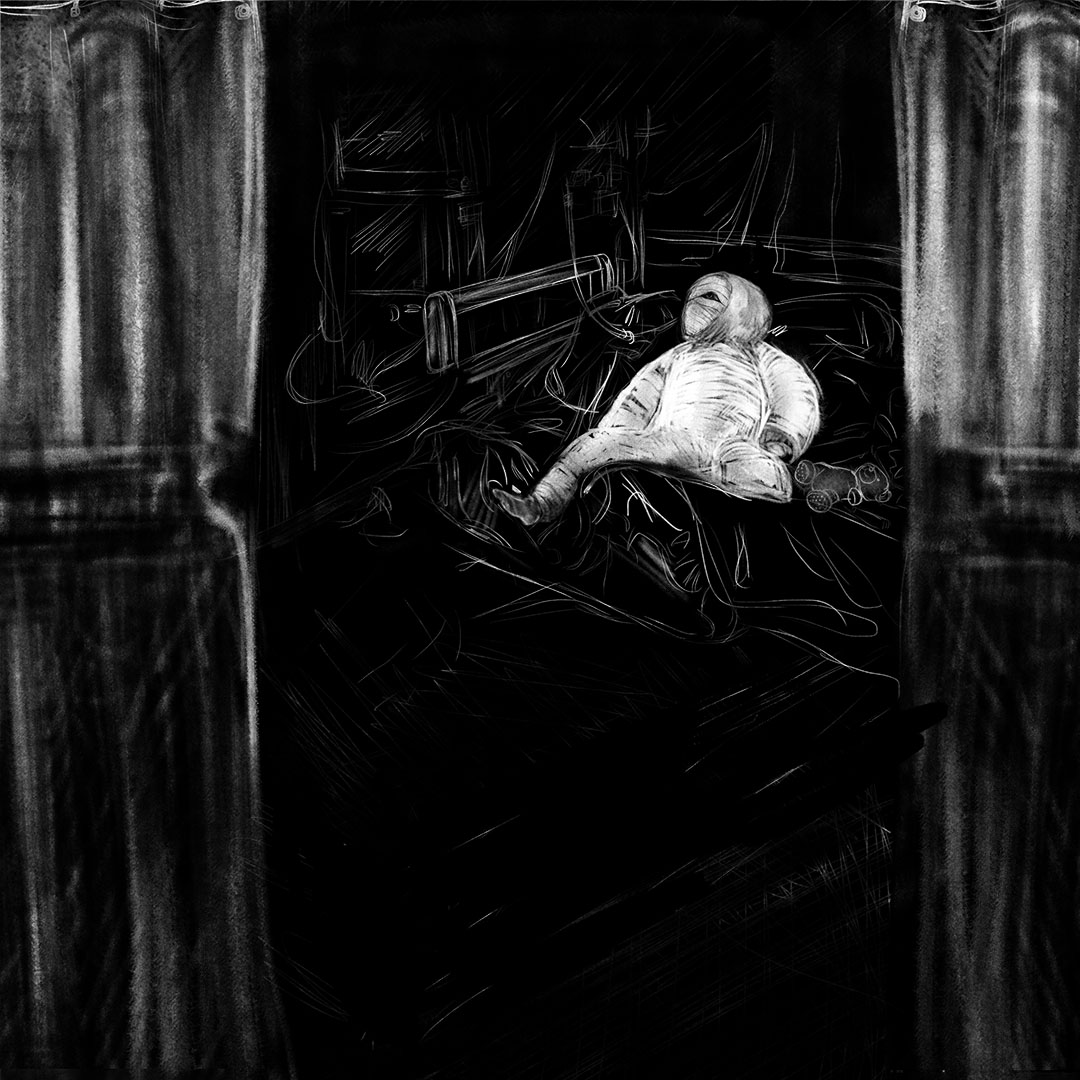

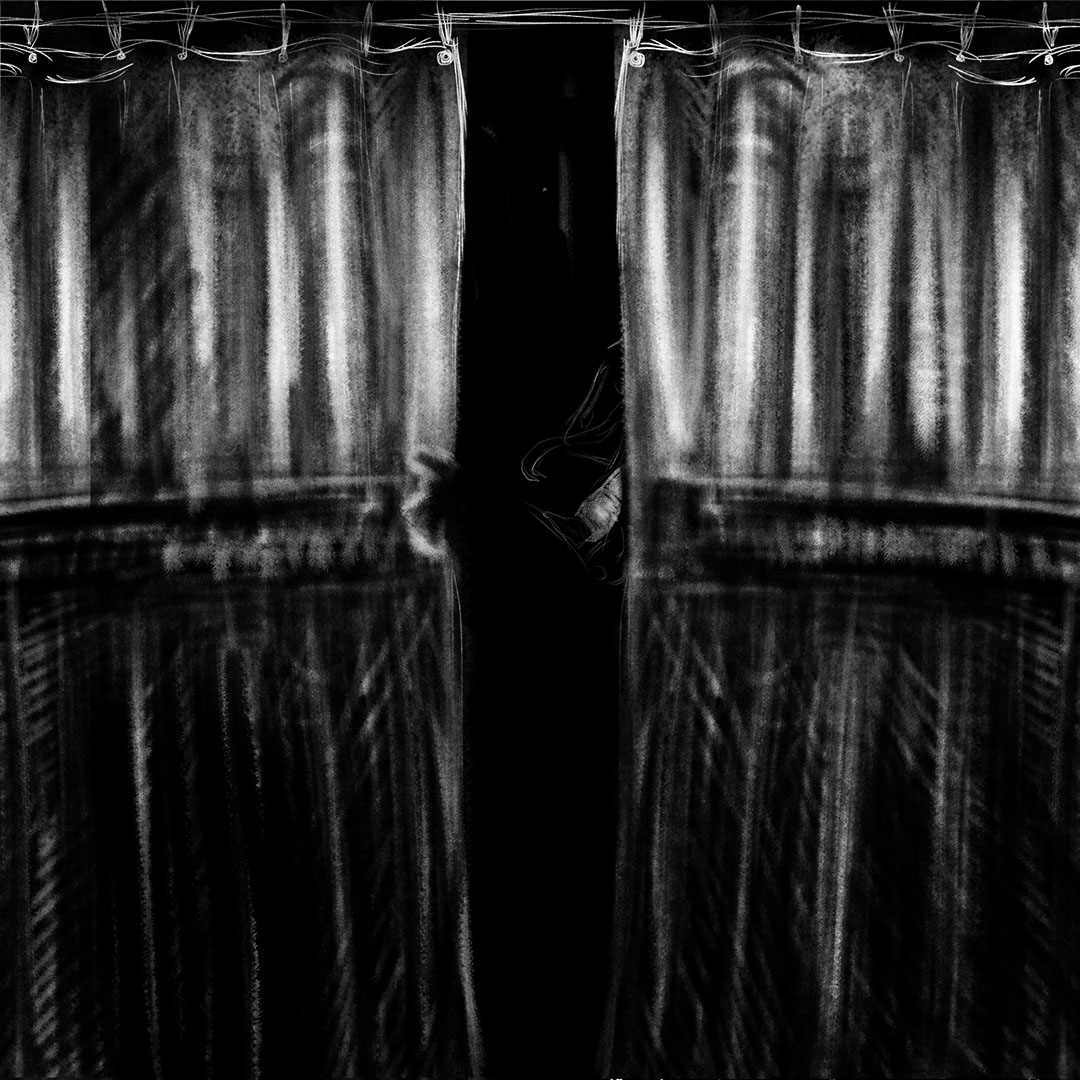

In September 2013, a U.S. drone strike in Afghanistan’s Pech Valley hit a vehicle carrying a family returning from buying flour. Inside were four-year-old Aisha Rashid, her parents, and her baby brother. Over twenty minutes, five missiles reduced the vehicle to a twisted metal husk.

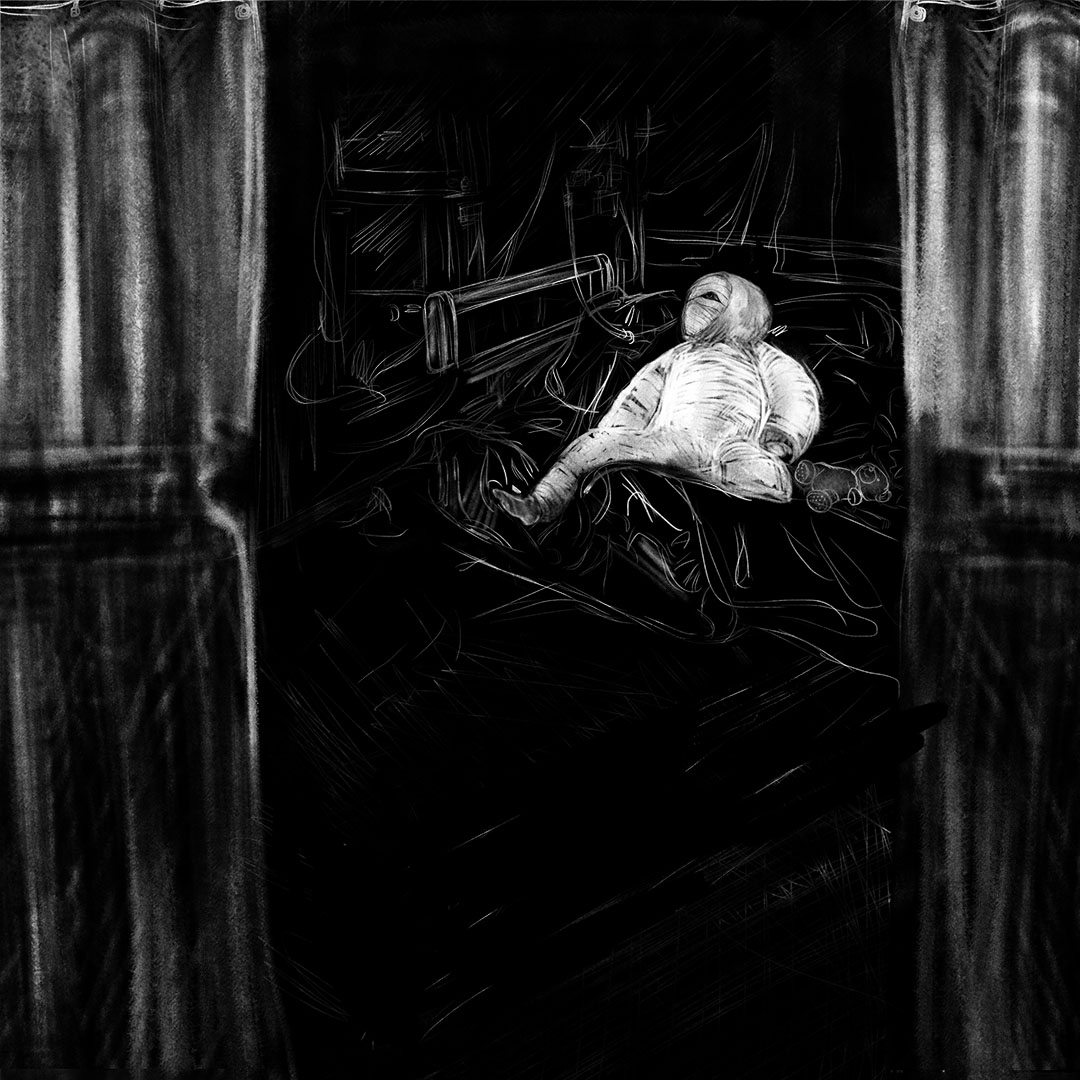

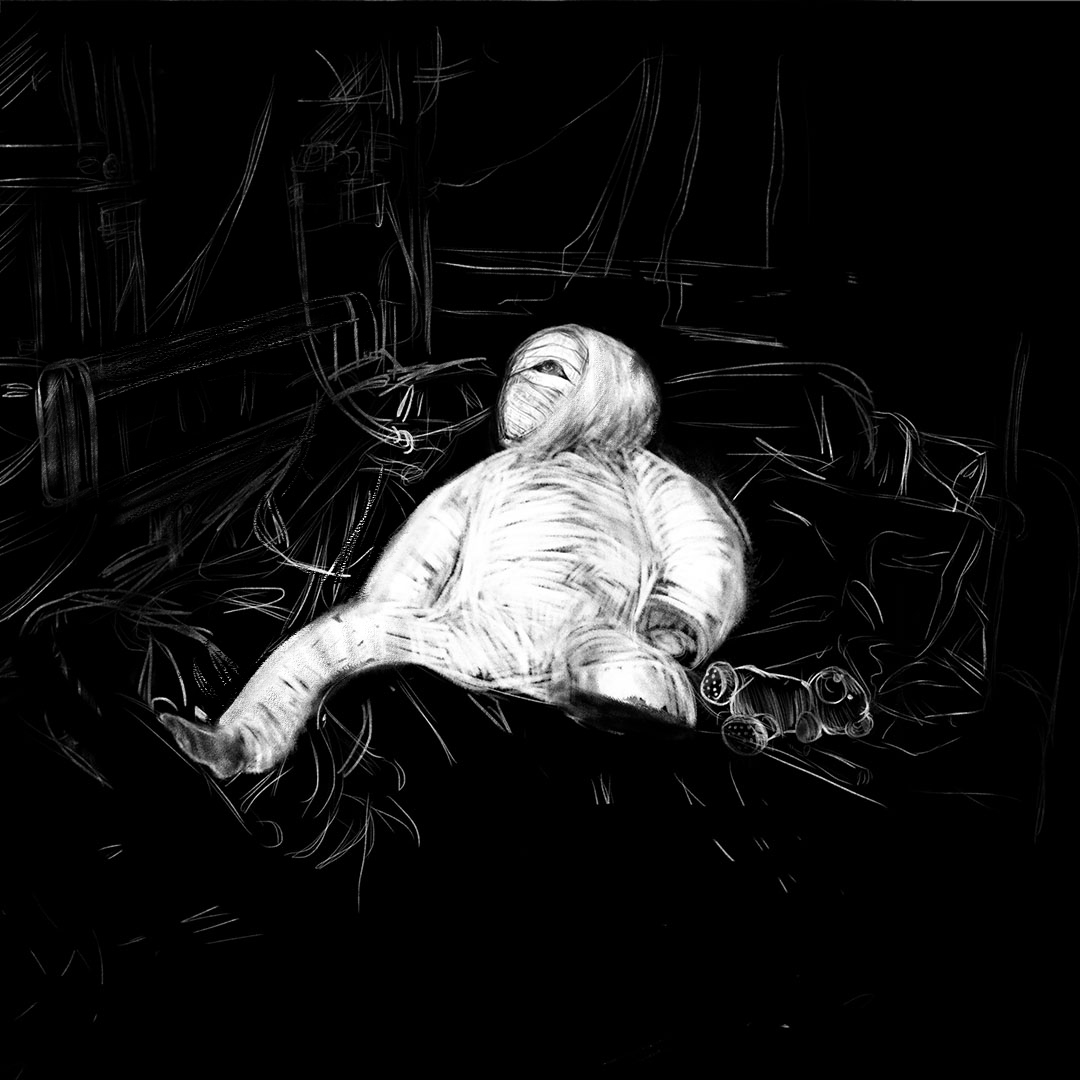

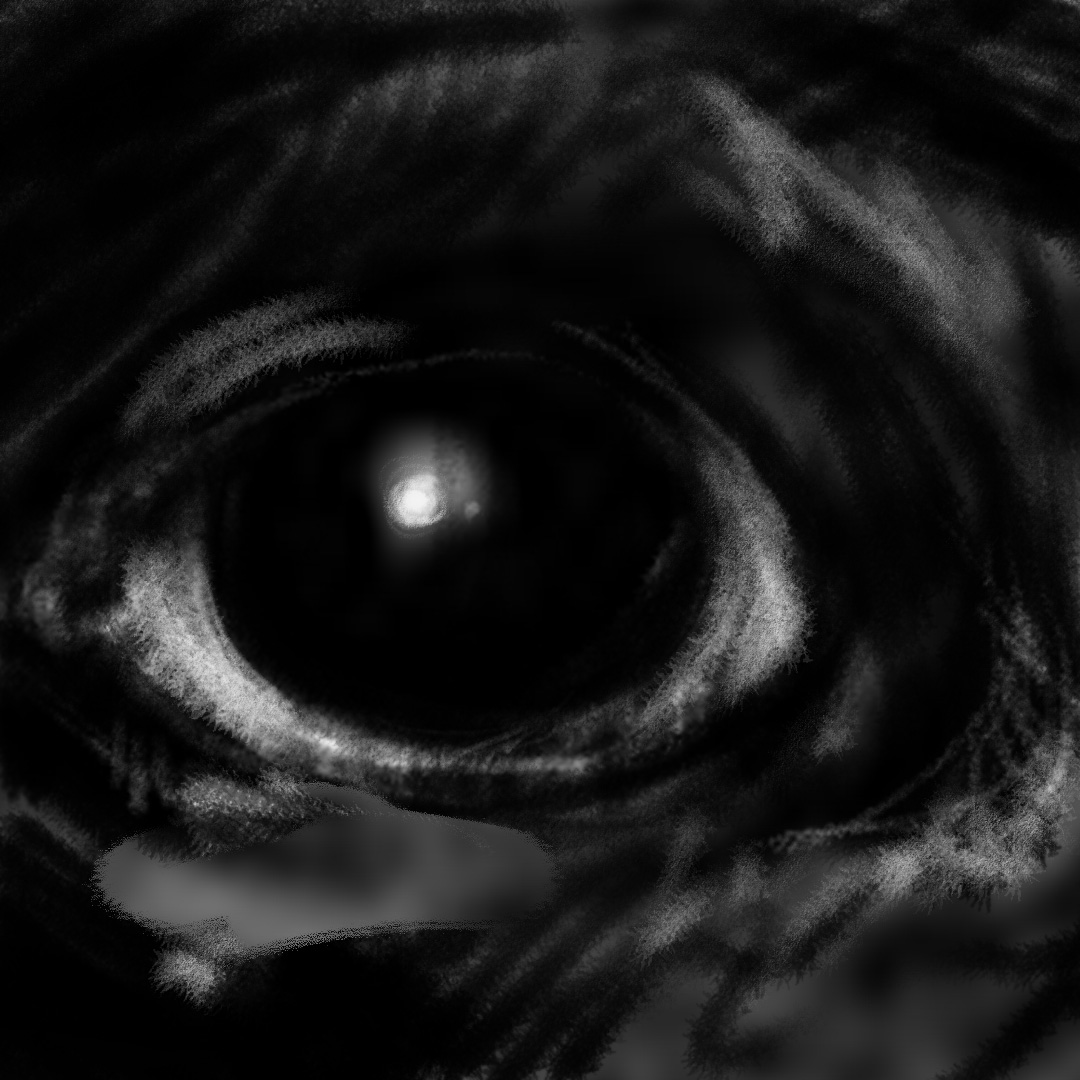

Only Aisha survived. Her face was severely mutilated, missing her nose, lips, stomach tissue, and left hand. Despite this, she managed to ask, “Where is my father? Where is my mother?”

She suffered extensive abdominal wounds, burns, brain trauma, and profound facial damage. She was moved through three hospitals: Asadabad, Jalalabad, and finally a NATO-run facility in Kabul. There, Afghan President Hamid Karzai and his national security adviser met her. The doctors bluntly told them there was ‘nothing there’ behind the gauze on Aisha’s face. The adviser wept openly, calling it “the most shocking thing I’ve seen in this war.”

Twelve days later, without notifying her extendee family, U.S. military officials transferred Aisha to the United States through the charity Solace for the Children. Her family learned only later that she was at Walter Reed Army Hospital in Maryland. Soon after, she vanished. The U.S. military internally acknowledged an “IM aerial attack” but did not release its findings. Desperate family inquiries into where Aisha had been transferred to received no response.

A 1993 Iraqi identity card for Abeer Qassim Hamza al-Janabi, age two.

Photo: Reuters

Abeer Qassim al-Janabi

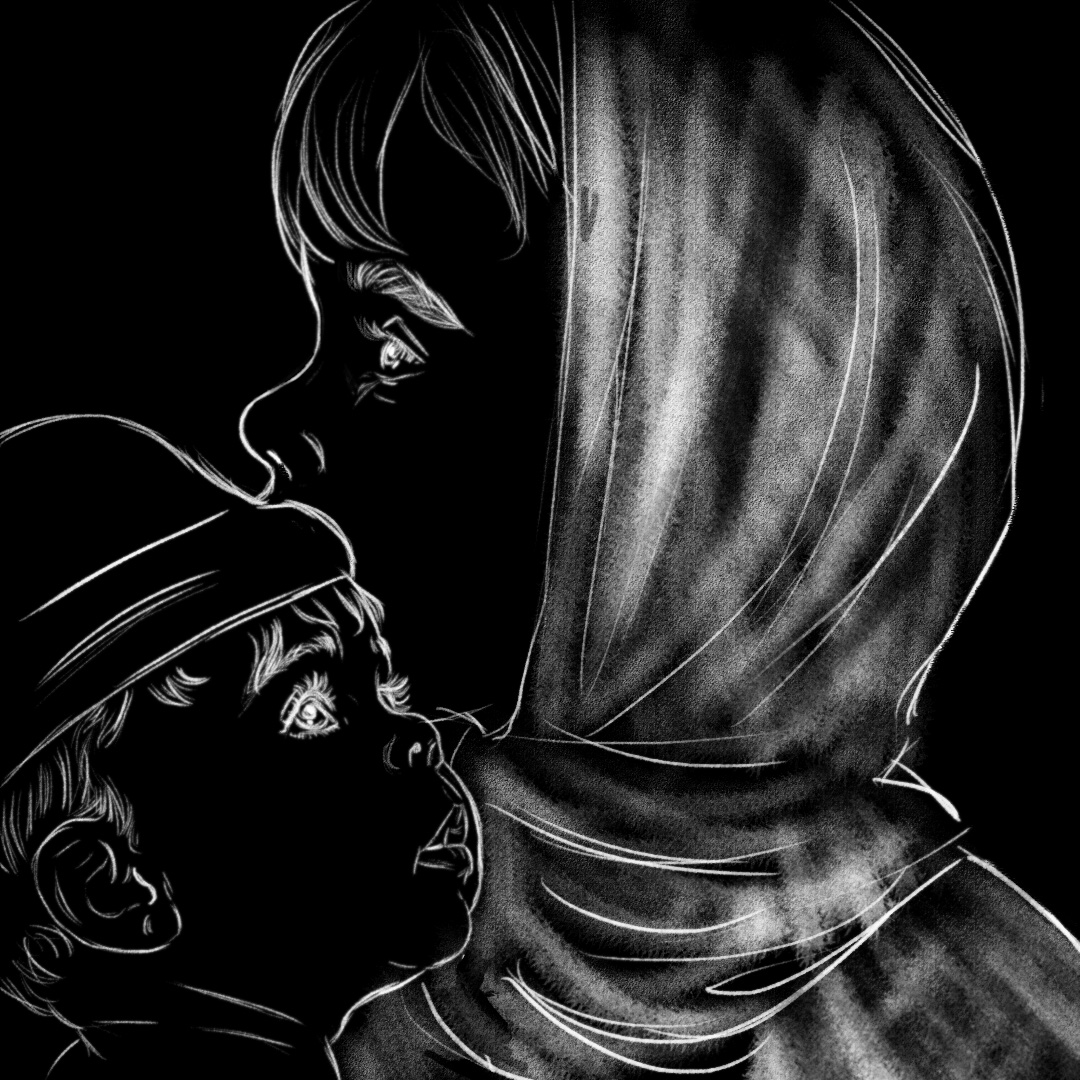

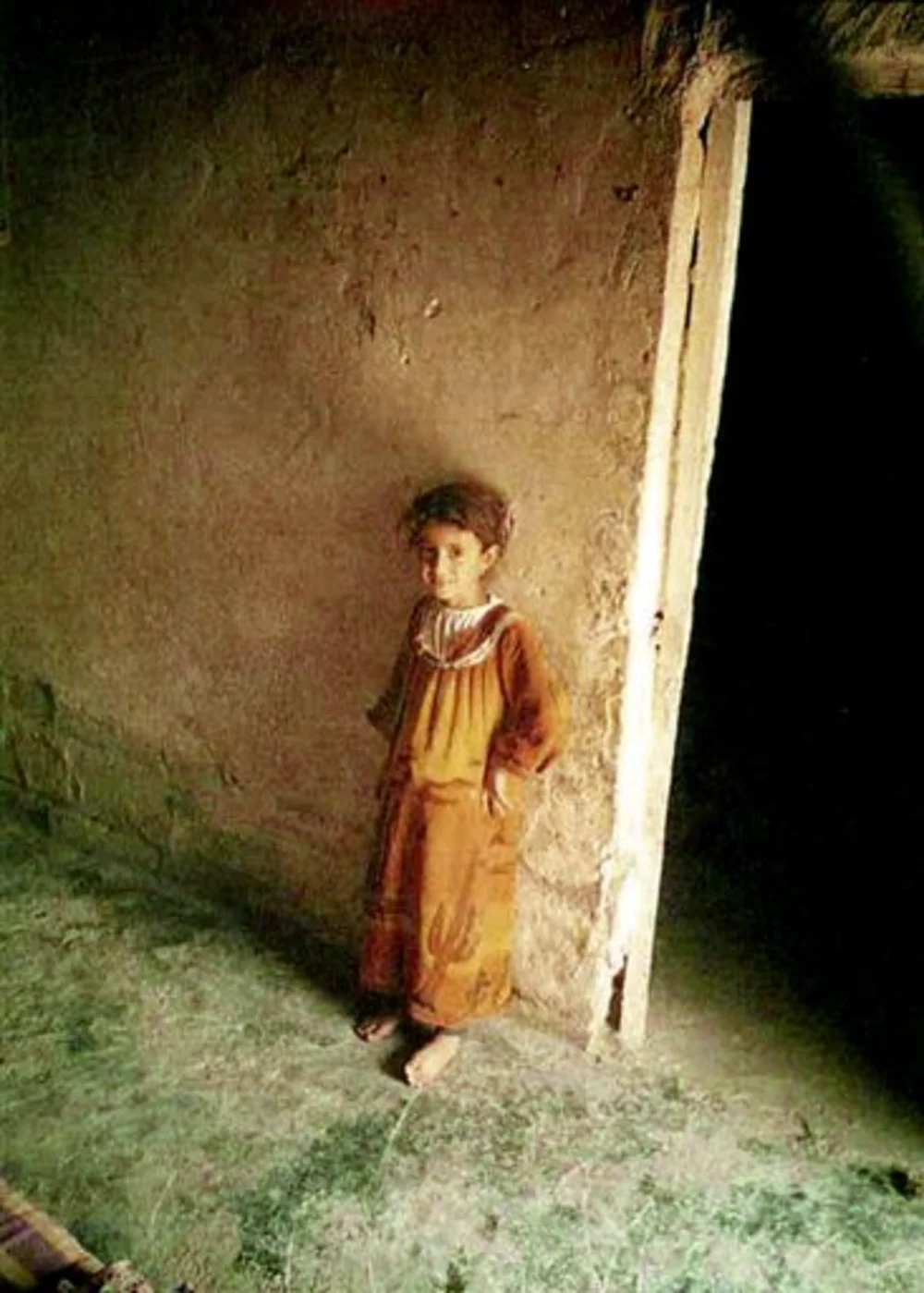

In the Iraqi village of Yusufiyah, 200 meters from a U.S. military checkpoint, fourteen-year-old Abeer Qassim Hamza al-Janabi lived with her parents and three siblings. Their rental home was on edge of the village, watched over by American soldiers.

The al-Janabi family was full of hope for a better future. They dreamed of owning their own home. Abeer’s parents worked hard to ensure their children received a good education. Kassem al-Janabi, a slim man whose wedding photograph showed him in a slightly too-large suit, was so devoted to family that he named his daughters after his sister’s children. He chose the name Abeer, meaning “fragrance of flowers,” for his eldest, and Hadeel, meaning “sound of the water,” for Abeer’s little sister.

Kassem was known for doting on his children when he was not working as a guard in an orchard of date and palm trees. He was determined to make his simple dream a reality: to live like other people, to own a house one day, and to see all four of his children finish college. His wife of twenty-five years, Fakhriya, was described by her sons and neighbors as a good cook and stay-at-home mother who longed for furniture that was not borrowed. All six family members shared a single bedroom.

Abeer was a quiet but otherwise typical teenager. Dedicated to her studies, she dreamed of living in the big city of Baghdad one day. Family members described her as tall for her age, slender, pretty but not strikingly beautiful – an ordinary intelligent girl, as her uncle put it. Soldiers who would later testify at Sergeant Steven Green’s trial claimed she looked older than her early teens, with one estimating her age at around twenty.

There are only two photographs of Abeer known to exist.

One is on an Iraqi identification card, issued in 1993 when Abeer turned two. The black-and-white image shows a beautiful child with dark eyes as big as eagle’s eggs. Her expression is both cautious and curious. Even at this age, hypervigilance would be already hardwired into her.

In the other photo, she stands barefoot at seven years old against the rough wall of the family’s rental home. The room is bare and dim, the green floor swept but worn. The light catches the soft folds of her handmade saffron-colored dress. Her small frame seems even slighter in the shadows. A solemn child with a shy smile, her hands tucked at her sides. Even at seven, she would have understood the weight of her family’s hopes and the difficulty in achieving them. Her name spoke of gentleness and beauty in a harsh place. In this photo, you can see a child trying to be good, trying to stay small and safe.

Neighbors and family recalled how the soldiers quickly took interest in Abeer. At first, they merely leered at the shy teenager. Whenever she tended the family’s garden, they stared at her from the checkpoint. Soldiers manning the gate stopped just to look at her. It wasn’t long before they tried to touch her. One day, Sergeant Steven Green approached and ran a finger down her cheek. Her mother spoke of soldiers giving thumbs-up gestures as they watched Abeer walk home, mocking her with Borat impressions and chanting “very nice.”

Shortly before her death, Abeer confided to friends how afraid she was of going outside. The soldiers made her not want to go to school. Her mother warned her father about this increasingly bad behavior, but they both knew that there was little they could do about it. Who would they even talk to? You risked death whenever you approached the soldiers first, and whenever they stopped you at random, their interrogation always took priority over your concerns.

On March 12, 2006, Sergeant Green and Specialists Paul Cortez and James Barker left their checkpoint in civilian clothes, reportedly in “ninja” gear and carrying weapons. It was a sunny afternoon when they broke into the al-Janabi home. They separated Abeer from her family, locking her parents and Hadeel in one room, dragging Abeer into another.

Green executed Abeer’s parents – her father shot in the head, her mother in the chest, and Hadeel, age six, in the face. As Green murdered her family, Cortez and Barker held Abeer down and raped her. Green joined in later. When they were finished with their fun, Green shot Abeer in the head.

After smashing Abeer’s skull with the butt of an AK-47, they doused her body with petrol and set it on fire before leaving to celebrate their secret mission. They burned their clothes and disposed of the murder weapon in a canal. Later that night, they shared a plate of chicken wings.

The fire spread through the room, alerting neighbors who called her uncle, Abu Firas Janabi, the first family member on the scene. “The poor girl,” he testified in court, “she was so beautiful. She lay there, one leg stretched out and the other bent, her dress lifted up to her neck.”

The soldiers tried to blame the attack on Sunni insurgents first. Eventually, evidence emerged after two platoon members were killed in retaliation. Green, discharged before the crime came to light, was prosecuted in civilian court, sentenced to life without parole, and later died by suicide in 2014. Cortez and Barker received sentences of 100 and 90 years.

Abeer’s brothers, Ahmed, age nine, and Mohammed, age eleven, survived since they were at school. In court, they described returning to a burned-out home, how the neighbors tried to stop them from seeing their murdered family, the sight of their gentle older sister’s charred corpse. “I refuse to go back to school,” Ahmed testified, “I do not have the mood to study.”

An undated photo of Nika Shakarami shortly before her death.

Photo: Reuters

Nika Shakarami

In September 2022, seventeen-year-old Nika Shakarami went to a “Woman, Life, Freedom” protest in Tehran after Mahsa Amini’s death. She texted a friend that she was being chased by plainclothes agents – then, she vanished.

Ten days later, her family learned a body matching her description had been pulled from the Kahrizak morgue. Authorities offered contradictory explanations, claiming she fell from a building despite reports that her skull had been repeatedly struck with a blunt object.

Iranian state TV aired footage allegedly showing her entering a building before her death, a claim her mother rejected. Leaks to the BBC described her being abducted, briefly imprisoned at Evin, resisting sexual assault, then killed by security forces and dumped beneath a highway. Her uncle said police smashed her skull, fractured her nose beyond recognition, and punctured her head, stark evidence of deliberate violence.

Her family’s grief turned to defiance. Authorities reportedly stole her body, burying her far from Tehran to prevent a large funeral. At a small ceremony, mourners chanted protest slogans as security forces attacked them with tear gas.

Investigations have multiplied, but official accounts remain fractured and contradictory. State outlets promote suicide or accident theories, while international media highlight leaked files saying she was killed for resisting sexual assault. The regime has run disinformation campaigns and coerced televised confessions from her relatives.

Yet despite all efforts to erase her, Nika’s memory endures. Weeks before her death, she appeared in a secretly filmed video, singing a classic love song and “My Heart Will Go On”. She sang openly and joyfully even though performing in public is banned in Iran.

These digital footprints – youthful, brave, forbidden in their power – still linger, but the fact remains that she is just one of many young people that the regime has eaten alive, bones and all.

Five year old Samar Hassan after her parents were killed by U.S. Soldiers in Iraq.

Photo: Chris Hondros, 2005

Samar Hassan

In the Iraqi city of Tal Afar, dusk fell fast in January 2005. The Hassan family was on their way home from a hospital visit in Mosul, crammed into an old red sedan.

Hussein Hassan, a father of six, drove with weary determination along the rutted roads, his wife Kamila beside him, the children pressed together in the back seat. They had little choice but to travel late. As usual, the hospital was overwhelmed. Trips between cities were dangerous, but what else could they do? Hussein just wanted to get his family home safely before the dark swallowed everything.

U.S. soldiers from the 25th Infantry Division were setting up a temporary checkpoint at the outskirts of the city. The area was tense. Rumors of suicide bombers swirled among the troops. The soldiers had orders to be cautious, to use warning shots if necessary. They had signs written in Arabic, but in the near-dark and the dust they were nearly unreadable.

As the Hassan family’s car approached, soldiers raised weapons. They fired a warning shot. The car kept coming. Another shot. Then a sudden hail of automatic fire tore through the windshield. Bullets smashed into the front seats, instantly killing Hussein and Kamila where they sat. The vehicle swerved and rolled to a halt in the dirt, the engine still running.

Inside, the six children screamed. Blood soaked the seats. Samar’s older brother, eleven year old Rakan, was struck in the spine and would never walk again. Samar, just five, was unhurt except for minor cuts. The other siblings clutched each other and wailed. They had left the hospital just hours before; their car was now a coffin.

War photographer Chris Hondros was with the American patrol that night. When the firing stopped and the soldiers approached, Hondros stepped forward with his camera. He would later describe the soldiers’ shock at seeing the crying children climb out of the car. One of the soldiers wept. The camera did not flinch.

Hondros photographed Samar moments after she climbed out of the car. In the photograph, she stands screaming, face twisted in a frozen howl of horror, arms and dress soaked in her mother’s blood. A single of streak of blood looks like a fat teardrop, snaking down the side of Samar’s face. A perfect picture of why war is hell.

The picture was published worldwide. It won awards and was praised for forcing viewers to confront the human cost of war. For Samar herself, there was no such distance. The little girl in the photograph had to go on living. In interviews years later, she said she didn’t even see the picture until 2011. When she finally did, she remembered exactly how it felt. “No one helped us after the death of my mother and father,” she said. “No one had any mercy on us or gave us a penny.”

The official investigation cleared the soldiers of wrongdoing. They had followed the rules of engagement, the Army said, given two warning shots. It was dusk. The car kept moving. It might have been a bomb. The war demanded caution over certainty. Still, the rules did nothing to fix what had happened. The surviving children received about $7,500 in compensation from the U.S. government, plus roughly $10,000 in donations collected later.

Rakan was flown to Boston for treatment in 2006 after the advocacy of aid worker Marla Ruzicka. He learned to use a wheelchair and gave interviews to reporters about his dreams of becoming a doctor one day, In 2008, while playing outside in Mosul, he was killed in another bombing.

Samar grew up near Mosul with relatives. She stayed out of school for years. “The girl in the photo”, a name she never wanted, was too well known for the past she wanted to forget.

For Hondros, the photo cemented his reputation as one of the defining war photographers of his generation. Critics and readers praised his unblinking eye. The image was called iconic, unforgettable, a necessary confrontation with the true nature of occupation. Hondros himself was killed in 2011 while covering the conflict in Libya. After his death, the Chris Hondros Fund was set up to support photojournalists committed to covering conflict zones with honesty and courage.

For the Hassan family, the photograph is not history or art. It is the moment everything ended. It is the moment Samar’s childhood became something to survive.

Eleven year old Samar Hassan in 2011.

Photo: The New York Times, 2011

How to Not Disappear

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Mauris sed dolor malesuada mi faucibus interdum id quis justo. Maecenas at aliquet tortor. Morbi semper suscipit mauris ut sollicitudin. Phasellus ex sapien, maximus nec maximus at, condimentum quis mauris. Vestibulum ante ipsum primis in faucibus orci luctus et ultrices posuere cubilia curae; Vivamus quam mauris, maximus at convallis non, scelerisque vitae felis. Suspendisse sed posuere mauris. Maecenas egestas fermentum nunc, vitae mattis arcu rutrum nec. Cras sit amet varius tortor, volutpat pretium magna.

Vestibulum eget mollis nisl. Proin bibendum ultricies mauris, sed facilisis velit fermentum in. Praesent quis gravida ipsum. Pellentesque a tincidunt est. Nulla mauris felis, congue quis ipsum at, facilisis feugiat mi. Duis posuere rutrum bibendum. Sed fringilla libero metus, at accumsan quam volutpat in. Donec viverra id velit non imperdiet. Donec ullamcorper felis sit amet urna lacinia facilisis.

Quisque condimentum sed nibh nec euismod. Nullam sollicitudin lobortis ante, nec hendrerit urna venenatis ut. Praesent vel sodales quam, quis hendrerit lectus. Maecenas semper felis sem, non interdum leo varius non. Etiam lacinia nisl nec nulla convallis bibendum. Praesent vel cursus eros. Aliquam risus ante, egestas eget egestas et, gravida sed quam.

Vivamus ipsum risus, dictum in sapien vel, vehicula congue justo. Cras quis nibh tincidunt, rutrum nisl quis, maximus risus. Ut posuere justo velit, at lobortis lacus ullamcorper vel. Curabitur nec mi in nunc blandit semper. Proin lobortis lacus ut vulputate pellentesque. Integer faucibus consectetur libero, vitae interdum metus. Phasellus varius mattis urna, vitae convallis lectus fringilla sit amet. Vivamus non purus sed ex congue lobortis. Sed in sagittis lacus, sed faucibus massa. Nunc ac justo quis nisi commodo ornare at sed nunc.

Duis tincidunt dolor at tincidunt iaculis. Suspendisse viverra nulla elit, et malesuada neque condimentum ut. Pellentesque ullamcorper arcu sit amet augue sodales, vel sagittis est sollicitudin. Aliquam vestibulum ac metus vel faucibus. Integer gravida faucibus urna, ut tristique felis eleifend a. Donec volutpat augue odio, non cursus mi accumsan interdum. Sed eget rutrum felis, sed auctor est.