Robin Hobb Isn’t Writing Back Anymore

Jump directly to specific sections of this article

using the links below.

Read Time

30 min

Where Is Robin Hobb’s Live Action Adaptation?

“Robin Hobb’s books are diamonds in a sea of zircons.”

– George R.R. Martin

I rarely read fantasy as a child. When it came to my library picks, it was usually a stack of Eyewitness Books, short stories by Flannery O’Connor, and anything about dogs. Dragons, royalty, witches, and magicians in faraway lands didn’t interest me at all. I wanted to understand the world, not escape it.

As an adult, my husband and I started our own book club. Assassin’s Apprentice, Hobb’s debut book, was our first read together. Every night, we binged multiple chapters in cozy silence.

Having read the series multiple times, my husband knew every plot point like the back of his hand. Watching me out of the corner of his eye, he enjoyed my reactions to certain scenes. There was one that made me put down the second book of the series for two weeks. He smiled when I picked it back up, finally ready for more.

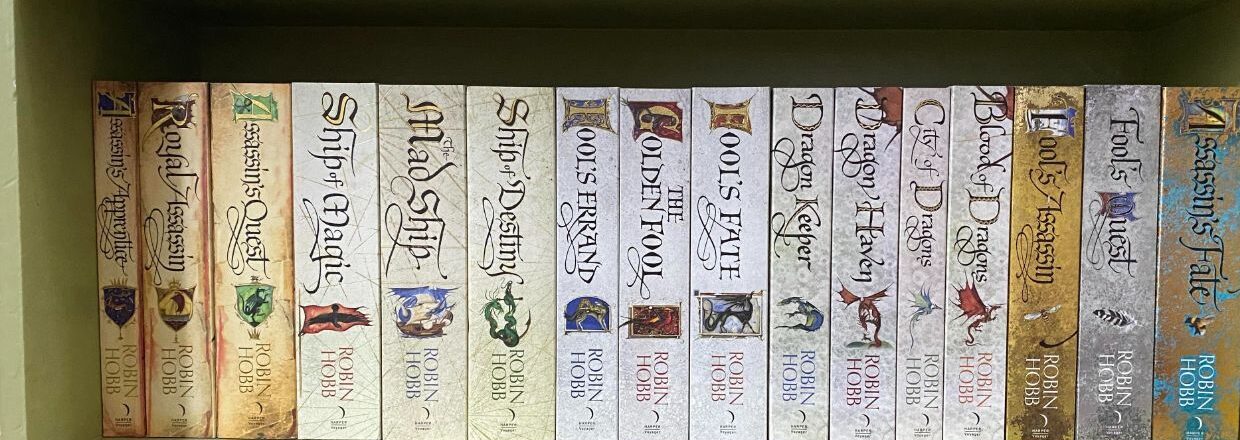

As of 2025, Robin Hobb has written 27 books, most of which are part of her extensive fantasy series, The Realm of the Elderlings, a collection of sixteen books published in five parts. Assassin’s Apprentice was published in 1995, the first of her famous Farseer Trilogy series. Twenty-one years later, the trilogy concluded with Assassin’s Fate.

The series follows Fitz, a royal bastard with a soft spot for animals. Whether engaged in a psychic battle or fighting soulless hate-zombies with an axe, his inner monologue is always relatable in the wildest scenarios.

When we meet Fitz in Assassin’s Apprentice, it’s during his first memory. His grandfather is dragging him through a snow storm towards a castle door. Fitz can’t see his mother but can hear her behind them. She’s sobbing, begging her father to not do this. After telling a stunned castle guard that he refuses to feed a prince’s bastard anymore, his grandfather turns on his heel and leaves. The shivering little boy staring at his back is no longer his problem.

Fitz will eventually forget his mother’s face. As an outcast with royal blood in his veins, he will learn to survive by being a tool for his King. One uncle wants him dead, the other pities him. His new guardian, a former friend of his father, is a tortured alcoholic. At night, a pock-marked old man comes out of the walls, whisking Fitz away to a study that’s cozy as it is messy. The old man teaches him how to get away with murder and loves a good mind game. Fitz is six years old and likes puppies.

The geography of Fitz’s world is not a backdrop in Hobb’s work. It’s a living entity, full of sight, sound, taste, and cinematic color. When asked about her worldbuilding inspirations, Hobb traces its roots back to real geography. Buck, the coastal duchy central to much of the series, draws heavily from Kodiak, Alaska, where Hobb once lived. The steep cliffs, seismic activity, bustling fishing ports, and the unique blend of fisherfolk, merchants, and military personnel all mirror the Alaskan town.

Speaking of fish, let’s talk about the food. The only thing better than a Redwall banquet is a bowl of stew in the Six Duchies. From Fitz sneaking sausages from the pantry to royal feasts featuring various cuisines, these many tasty scenes inspired an Instagram account (@recipesfrombuck) dedicated to recreating dishes from the series.

Hobb’s approach in writing about food is simple but effective. “We have five senses, and in a description of anything, I want to engage as many of them as possible,” she said. Food offers sight, taste, smell, texture, and sometimes sound. She maintains geographical consistency, ensuring ingredients match what would actually grow in each region, though she admits to enjoying the occasional imported luxury like ginger root.

Farseer Trilogy introduces two distinct magical systems: the Wit, which allows spiritual bonding with animals, and the Skill, a powerful form of telepathy. Fitz possesses both. Hobb originally envisioned a more complex “circle of magics” that would include hedge magic and scrying, intersecting like colors on a wheel.“A tale of three magic wishes works well; an infinite number of wishes is no story at all.”

The key, she found, is limitation. In her world, magic requires effort, practice, and adherence to strict rules. Having natural talent is just the starting point; the real work comes in training and development.

Fitz as an adult is a product of his environment. For most of the trilogy, he considers himself nothing more than a tool to be used. He earns his keep as a royal assassin (at first), but he also has a rich inner life that craves kindness, love, and peace. He enjoys writing and illustrating history books in his spare time. He’s respectful to all, especially his targets. After saving a chubby dog from choking to death, he secures a coveted political alliance.

As he grows into a man, his gentler side cultivates lifelong allies. Unlike the archetypal lone hero, Fitz wants to stay close to his loved ones. Even when he isolates himself from them for years at a time, he wishes he could be by their side, dining on beef and beer. He is tethered to his duties as an assassin, his various father figures expectations, the eccentric woman that fully embraced him as her son. He’s best friends with a wolf and a fool.

This web of relationships creates a constant tug of war for Fitz’s soul. One father figure demands he give up his magic. Another father figure insists he surrender his will and follow orders, regardless of personal ethics. Both expect him to fulfill his duty, but their visions for what that duty entails couldn’t be more different.

Then there’s the women who love him. For Kettricken, a fish out of water princess turned quietly powerful queen, Hobb drew from historical female leaders who prioritized service to their people over personal desires. Molly, a controversial character in the fandom, is the woman that Fitz loves yet isn’t the one that most readers would choose for him.

Of all of Hobb’s characters, the Fool is a beloved fan favorite. The character first appeared in 1995, well before contemporary conversations about inclusive representation of any kind. This wasn’t a deliberate act of representation, at least not in the modern sense. In her original outline, the Fool had consisted of a single sentence, one line that delivered a crucial message before stepping back into the shadows. When asked about the character’s sex or gender, Hobb’s has a sensible answer:

“My characters come to me as who they are.”

Hobb’s writing journey offers practical wisdom for aspiring authors. When it comes to worldbuilding, she wishes she’d determined coinage and monetary values from the start. She also recommends establishing clear ways to convey the passage of time independent of characters’ lives.

Her most helpful practice? Maintaining a glossary where every proper noun goes in alphabetically with a brief explanation, anchored to a chapter or event rather than page numbers. It makes all the difference.

Wrapping up the writing of Assassin’s Apprentice really came down to the wire. “I looked up one day and the deadline was upon me!” Hobb recalled. Her teenage son helped with the read-through, proving invaluable by flagging unrealistic character behavior. She completed revisions while her youngest daughter watched Disney’s Beauty and the Beast on endless repeat.

Regarding potential live action adaptations, Hobb is cautiously realistic. While there’s currently no plan for a TV or film series, she knows that writers’ rooms would ultimately make decisions about which details to include. If an adaptation were to happen, Hobb would want it to follow the books exactly, the way Jody Houser’s Dark Horse comics adaptation has done. She chose to start with child Fitz in Assassin’s Apprentice because she believes it’s the best way to lead readers into his life and learn about the world through his growing awareness.

In a recent blog post, Hobb shared news that marks a shift in her relationship with readers. After decades of following Isaac Asimov’s example, replying to every first letter from a reader, she can no longer maintain this practice.

The reason isn’t lack of desire or volume of genuine fan mail. It’s something more insidious: her inbox now receives eight to ten emails daily that masquerade as reader letters. They start convincingly, mentioning specific titles and praising character development or political intrigue. But then comes the pivot: offers to promote her books for money, promises of increased orders, podcast opportunities, and various marketing schemes.

“I end up feeling like a sucker,” Hobb admits, describing how she’d send warm responses thanking readers for their feedback, only to receive follow-up emails revealing the true purpose: paid promotion services.

These aren’t organic connections; they’re AI-generated or bot-driven attempts to sell services she doesn’t need. The physical toll matters too. Hobb mentions her hands are too worn out and sore to waste keyboard strokes on bots and algorithms. She still has about six physical letters on the corner of her desk, real mail from genuine readers, and promises to get to them. Unfortunately, the email responses that once connected her directly to fans around the world have become unsustainable. “I am saddened that AI, which could be doing so much good in the world, is instead clogging up my email box and blocking real reader mail.”

For an author whose work explores the costs of connection, the Wit bond between human and animal, the Skill link between minds, this forced disconnection carries a particular irony. Hobb built her career on understanding how relationships shape us, how duty binds us, and how the ties between people matter more than power or magic. Now those very ties are being weaponized by algorithms that mimic sincerity to sell services.

Thirty years after its publication, Assassin’s Apprentice continues to find new readers. Those discovering Hobb’s work today will still find the same richly detailed worlds, the same flawed and beloved characters, the same food that makes you hungry. That said, they’ll also be reading an author who can no longer write back. Not because she doesn’t want to.

The letters she’ll never answer aren’t lost, though. That’s always been the real magic of books: not the response we might receive, but the conversation that happens in the quiet space between writer and reader, where a story can change a life without a single word passing back.

Sooner rather than later, I hope that Robin Hobb receives an email from a smart producer with deep pockets. It’s successfully sent to her inbox and not filtered into spam. This smart producer not only has the funds to create a live action television adaptation of the Farseer Trilogy, but they will give her full creative freedom. There’s an contract awaiting her signature in the DocuSign link below. Final say in casting, scripts, and director. A trailer on set, well-stocked with whatever she needs to make the magic happen.

Over the course of Farseer Trilogy, Hobb tells a story that speaks to what an abuse of power looks like, how childhood wounds can fog your worldview, the fluidity of identity, and how we can grab the reins of fate by being our own catalyst. Oh, and there are dragons too.

It deserves an eight episode run for the first season. Twelve, ideally.

Chatting with Robin Hobb

“I grew up fatherless and motherless in a court where all recognised me as a catalyst.

And catalyst I became.”

– Assassin’s Apprentice

Each city in the Farseer world feels like a character in its own right. The Six Duchies street scenes alone are pure sensory overload. Where did you draw inspiration for your geography?

I think that geography greatly affects story telling. I’ve lived in a number of small towns, in Washington and Alaska. Buck definitely takes a lot of geography from Kodiak, Alaska, and the geography definitely affects both places.

The steep cliffs, the seismic quakes that affect that region, the port for fishing vessels and trade, so much of Buck could be seen easily as Kodiak. Right down to the mix of fisherfolk, merchants and the military!

The food in your books inspired Instagram account @recipesfrombuck. How do you write a scene to make it tasty as possible?

I think it goes back to ‘show don’t tell.’ We have five senses, and in a description of anything, I want to engage as many of them as possible. So, if there is food, there is sight, taste, smell, texture, sometimes the sound of it cooking. Think a sizzling steak or popcorn. I try to keep the menu to what might actually be growing and available in that type of area, though it’s fun to bring in something like an imported ginger root!

My favorite running gag is Fitz sneaking sausages from the pantry, or a nice heel of bread. In a live-action adaptation, can you please include moments like these?

The sad fact of that, from my very limited experience, is that the Writers Room would be making those sorts of decisions. From what I have heard, once the writer signs, the screen writers adapting the book take over. They are far more familiar with what you can and can’t do on a screen, how much time a scene takes up, the budget. All of those things – I hasten to add that right now, there is no offer or plan to make the trilogy into a series or movie.

The trilogy introduces two distinct forms of magic – the intuitive animal-bonding Wit and the telepathic Skill. What was the creative process behind these systems?

I had envisioned a sort of circle of magics. In addition to the Wit and the Skill, there would be other arcs, such as an arc of Hedge-Magic, and one of Scrying (which Chade could do) Like a color wheel, there would be places where the magics mingled, in different strengths and unusual ways.

I don’t think there is anything particularly original in the Skill, the idea of telepahty and being able to influence others via mind contact. And the Wit, or people being able to speak to animals, is also an idea used in many stories. I still love the idea of those magics.

What challenges did you face in keeping the Wit and Skill believable?

It is essential, in my opinion, that magic have limits in a story. A tale of three magic wishes works well; an infinite number of wishes is no story at all. I am always disappointed in a story that tells me ‘the magic can’t do that’ until, at a critical moment, the magic user tries very hard and the magic does that! In the Farseer tales, the social limitations on the magic was also fun.

I also think it’s important that magic require effort and practice as well as being limited by rules. No one gets Something for Nothing. Having a predilection for gymnastics or magic is not the same as training and expanding your ability. The character has to put in time and effort.

Fitz’s journey is marked by deep internal conflicts and the weight of destiny. What do you hope readers take away from his evolution?

I’ve read many wonderful tales where the hero exists in a vacuum. The solo hero, like Conan, striding across the landscape having adventures is something I love. But most of us have parents, siblings, neighbors and pets. Just taking a weekend for ourselves might involve a tremendous amount of planning.

Fitz has duties to his family, to Chade, expectations from Burrich, hopes from Molly, and just as most of us do, he had to find a path through all that and try to claim a bit of his life for himself. I thought the reader might find that a point of identification.

Fitz's upbringing embodies the saying "it takes a village to raise a child." He found true support in Patience, his father's eccentric widow. After Chivalry's death, why couldn't Patience and Burrich take young Fitz to Withywoods? Were they prevented by personal history or court decorum?

Patience and Burrich have history. It involves Lacey as well, and I have quite a chunk of that tale written down. But in the end, I’m not sure it’s as interesting to a reader to read events when they already know what the final ending to that story would be.

The quick answer; Patience is and was wise enough to know it would never work out well. Burrich is the same. I think almost every adult has someone in the past that they love but could never live with.

Speaking of support, Fitz’s relationships with his mentors, be it Chade or Burrich, play a crucial role in his development. How do you write a mentor-mentee dynamic?

There is quite a tug of war there for Fitz’s soul. Each mentor puts limits on how Fitz must live. One says he must give up his magic, one says he must surrender his will and do what he is commanded, regardless of his personal ethics or doubts.

I think most people have faced those sort of divided futures. One parent wants you to go to college, one wants you to go into the family business. One thinks you must get married and have kids, another encourages you to have adventures and a great career. In Fitz’s case, both mentors expect him to do his duty. It’s not easy for him.

Kettricken is one of my all-time favorite characters. Neil Gaiman’s female characters have nothing on Kettricken. How did you conceive her? Would she and Etta get along?

I think there are a lot of historical female leaders who have put their service to their people ahead of personal goals and desires. Often they labor in the background and do not achieve the level of fame they might have if they were less focused on doing what was essential. I think that the great difference in ethics would make friendship between Kettricken and Etta difficult.

Molly is a controversial figure in the Farseer fandom. Readers love or hate her with little in-between. What are your thoughts on this?

Here’s an odd thought. For some readers, they want the protagonist to remain ‘available’. It’s much like with ‘boy bands’. As a teen, we dream that ‘he would choose me!’ and we don’t want to hear about his girlfriend or wife because it cracks that dream. So, for a certain number of readers, there would be that. For others, it would be ‘she’s not good enough for him!’

I feel Fitz chose the woman he wanted and needed. We don’t always like our brother’s girl friend or mom’s new boyfriend – it’s sometimes hard to watch a favorite character choose a mate we would not select for him or her.

Bees feature prominently in the trilogy. They show up everywhere. A character is named after them. Do consistent motifs like these just happen or were they a conscious choice?

Hm. I’d never considered that. The bees and Molly’s candle making and honey are the big connection, and also her reason for naming Bee. No symbolism or theme!

Fitz’s inner monologue is usually going through it. Outside of the trauma he goes through, he becomes a handsome man who has no idea how handsome he is. He is oblivious to how people see him. How did you approach crafting his mindset?

While Fitz is introspective and we share his inner thoughts and dialogue, not much of that introspection is focused on his physical appearance or on how others might see him. I think he gives most of his attention to surviving and coping.

He has been taught by Chade to be unobtrusive in many ways. To be an assassin or a spy, one must remain in the background. To most of the people important to him, he has a role to fulfill. He knows what he does well and takes satisfaction in it.

Beloved, or The Fool, is my second favorite character. Not only for their dialogue but for their representation of LGBTQ themes. Was this a deliberate choice in their character development?

The Fool first appeared in a novel in 1995. ‘Representation’ as we know it now didn’t exist then, so there was no intent on my part to be inclusive. My characters come to me as who they are. He stepped onto the stage, into the spotlight, and started talking. In my original outline, he had exactly one sentence.

His role was to deliver a message and step back. But he didn’t. So, the Fool is the Fool, and he stepped into the book as a whole person. When people ask me about his sex or gender, I ask, “Why does it matter?” I can’t create a character to order. I can’t say, “Oh, my, this book needs a gay character who is such-and-such a race and he must tick off these boxes. The character just steps out and there they are.

In a live action adaptation, such as a miniseries, what would you like to see?

In all honesty? I’d want it to follow the books exactly. Jody Houser has done an extraordinary job of this in the Dark Horse comics adaptation of Assassin’s Apprentice. I chose to start with child Fitz as I believe it is the best way to lead the reader into his life, to see the Six Duchies through his eyes and his growing understanding. That is probably why I doubt that it will ever see a TV or film adaptation.

How did you feel when you finished Assassin’s Apprentice?

I looked up one day and the deadline was upon me! So, I hammered on it every moment I could get free. My younger son helped me with the read through. He was 15 and was very good about saying, “No, he wouldn’t do that – no guy would do that.”

In a nutshell, what are some rookie mistakes to avoid when it comes to worldbuilding?

Things I wish I’d done? Determine coinage and value of money and stick to it consistently. Have a clear way to convey the passage of time, independent of the characters’ lives. Those would be my two big things.

Most helpful thing I learned to do? Make a glossary. Every time you use a proper noun, open up the glossary file and put it in alphabetical order, with a brief explanation. Page numbers won’t work, because they change. Use a chapter or an event to anchor it.