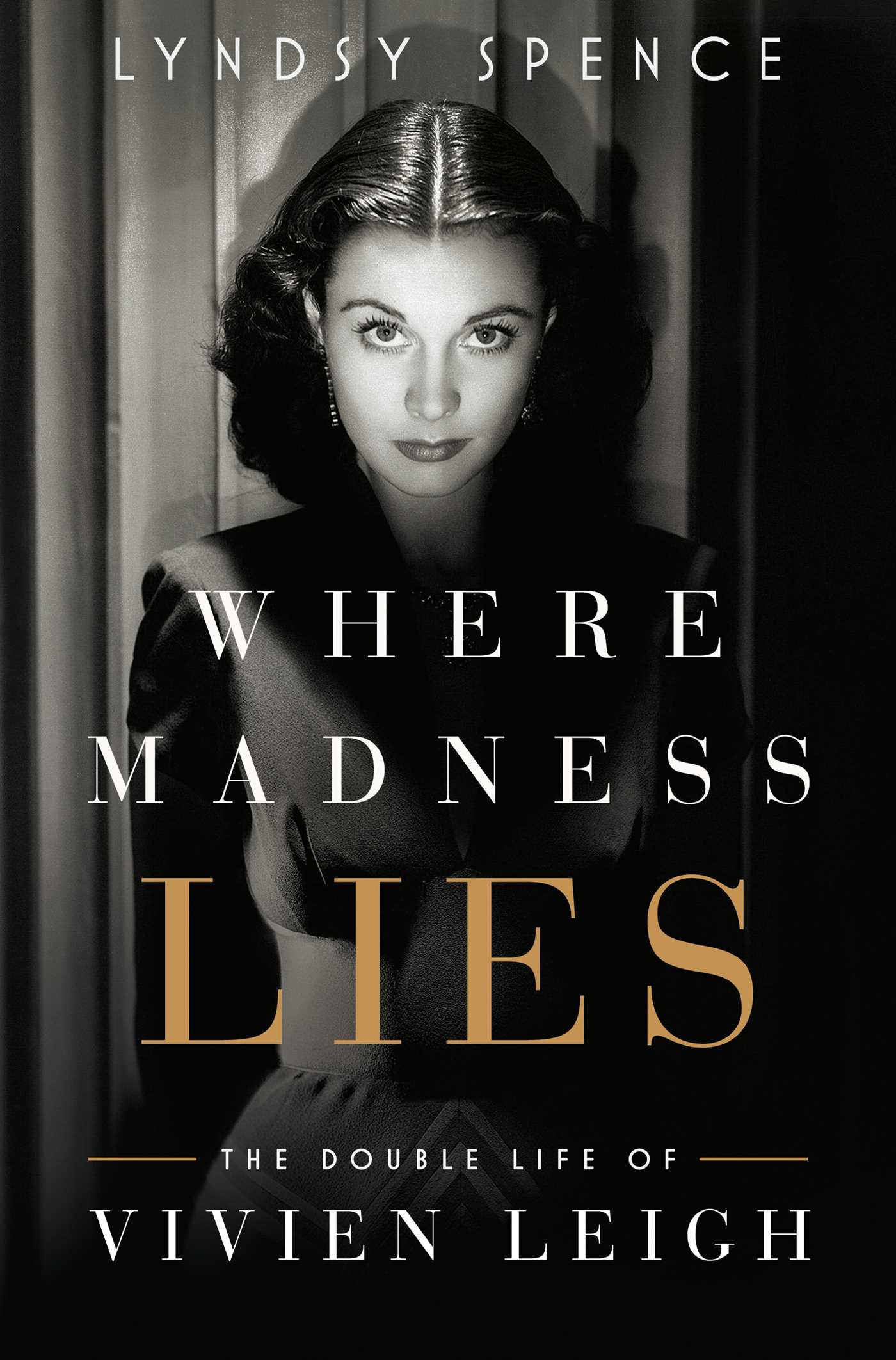

‘Where Madness Lies: The Double Life of Vivien Leigh’ by Lyndsy Spence

Where Madness Lies

The Double Life of Vivien Leigh

Author: Lyndsy Spence

Genre: Non-fiction biography

Publisher: Pegasus Books (2025)

Distributor: Simon & Schuster

Length: 256 pages

Jump directly to specific sections of this article using the links below.

Article Read Time

30 min

Meet the Viviens

“We didn’t know it then, but then how could we? It was there, though. Vivien would get along fine for a few weeks, a few months – be perfectly normal and friendly and involved in her activities. Then, suddenly, a complete turnaround. Sometimes it would last only a few hours, other times a day or more. But when it happened, we’d see a completely different girl.

Had she been a child today, someone would have taken serious notice and sent her to a doctor to be examined. Who knows what he would have discovered – a chemical imbalance, a genetic defect? I don’t know if there’s a name for what Vivien suffered from, but she definitely suffered from a mental peculiarity that would put her severely out of sorts. It was frightening when it happened, almost like a dual personality.”

– Vivien Leigh’s former schoolmate at the Roehampton Convent and Boarding School

To Laurence Olivier, there were two Vivien Leighs.

One was his Vivien – an enchanting vision who was wickedly funny and impossibly elegant. It wasn’t just that she was one of the most beautiful women in the world. A fiercely intelligent polyglot, her photographic memory and encyclopedic knowledge were stunning to behold. She loved animals, especially kittens, and was a loving stepmother to his son. His Vivien was perfect, with her exquisite manners and expensive perfume.

Then there was the other Vivien – the one that broke windows, chain smoked until she coughed blood, abused alcohol, had sex with strangers, bit policemen, barely bathed, attempted suicide, and tore into her loved ones with vicious profanity-fueled tirades, sobbing all the while.

In the first few years of their marriage, the other Vivien would appear for only a few hours, a day or so at most. As they grew old together, the longer the other Vivien stayed, sometimes for weeks or even months at a time. His Vivien would emerge only when the other Vivien went howling into the night. Begging for forgiveness and unable to remember anything, no one was more horrified by the damage left behind than she.

In Where Madness Lies: The Double Life of Vivien Leigh, author Lyndsy Spence offers an intimate exploration of the renowned actress’s life and her battle with bipolar disorder. Unlike traditional biographies, Spence zeroes in on the last thirteen years of Vivien’s life. More importantly, she does not censor the uglier side of Vivien’s disease.

Opening in 1953, the first chapter delivers a riveting, blow-by-blow account of Vivien’s spiral into one of the worst nervous breakdowns of her life on a movie set in India. The Vivien in this chapter is the worst version of herself, snarling at toddlers and making David Niven’s life absolute hell. After being forcibly sedated and escorted back to London by Laurence Olivier, she was involuntarily committed to a psychiatric hospital.

After being dropped off by her husband at Netherne Asylum, Vivien was immediately stripped of her clothes, given an ice bath, and medically induced into a coma. She occasionally woke from her coma to find herself strapped down with a gag in her mouth, receiving electroconvulsive therapy. Weeks of this turned Vivien into a shadow of herself, hair singed and burn marks seared into her temples.

How did their glittering love story become their own personal hell? Larry constantly asked himself that yet never got an answer. At the end of his life, stumbling across one of her films on late night television was like a knife in his heart.

The greatest actor that ever lived, now just an old man crying in his most comfortable chair, asking where it all went wrong.

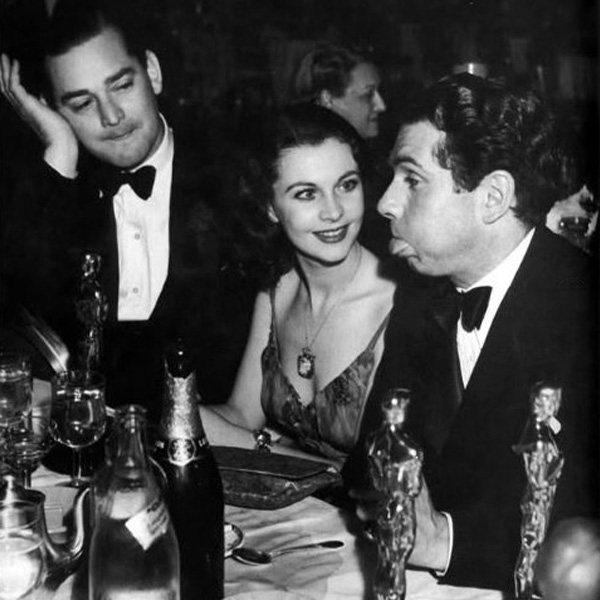

Vivien and Larry at the Academy Awards (1940)

The Oliviers after Vivien’s breakdown (1953)

November 5, 1913

“At first glance, the body in the bed meant nothing to Larry ; there was no spark of familiarity. The pale face, marked by the ECT, and the colourless eyes were that of a stranger.

A current of shock and fear surged through him but he could not express it. Everyone, including society, wanted him to be strong and face the challenge head-on. There could be no platform to convey his feeling;everything within the confines of their marriage, and beyond, was to be buried from public view. He would tell everyone that Vivien had to convalesce from tuberculosis. To be afflicted by tuberculosis was far more respectable than mental illness; a consumptive was more socially acceptable than a lunatic.”

– Lyndsy Spence, page 35 of ‘Where Madness Lies’

Vivian Hartley was born in India, the only child of Ernest Richard Hartley, a British broker, and his wife, Gertrude Mary Frances.

An exceptionally lovely little girl, she was primarily raised by her Ayah (nursemaid) while her parents pursued their own ambitions. Ernest was a charismatic philanderer who could tell one hell of a story and an even better lie. Even though he blatantly cheated on his wife, he loved Gertrude enough to resign from the renowned Bengal Club due to a rule prohibiting Caucasian members from having wives of a different race. Renouncing his social status may have planted a seed of resentment between Vivian’s parents. Both had multiple affairs throughout their marriage, yet they never divorced.

Gertrude’s relationship with Vivian was equally complex. A pursuer of perfection, prone to dark thoughts, mood swings, and delusions of grandeur, Vivian’s mother believed that beauty could be cultivated. While pregnant, she spent at least fifteen minutes a day staring out the window at the snow-capped Himalayas, hoping their majesty would manifest in her child’s appearance. She was proud of her vivacious daughter, especially when she recited Little Bo Peep letter-perfect in front of an adoring audience. Still, Gertrude was convinced that the child needed a proper English upbringing and education.

Off Vivian went to Roehampton Convent and Boarding School in England. Only five years old, she was two years younger than all the other girls at the convent school. The little girl barely saw her parents over the next decade – Gertrude once a year, Ernest every two.

Convent life was conservative and spartan, to the point that the girls were required to wear long linen shifts whenever they bathed in tubs of cold water. Since Vivian was the only girl at the school that didn’t go home for the holidays, the Mother Superior gave her a kitten out of pity. Later in life, Vivien would credit this cherished pet with ‘saving her reason’.

The beauty Gertrude cultivated during her pregnancy became a burden on her daughter’s small shoulders. When groups of older boys loitered around the school’s gates, wanting a glimpse of the pretty girl they heard about, the nuns blamed Vivian. During the occasional beach trip, she would emerge from the ocean in her bathing suit to find those same boys standing on the shore, staring at her. This pack behavior branded her with a nickname – the little temptress of the Côte d’Émeraude.

During a rare visit back home, Gertrude’s boyfriend at the time made sexually inappropriate advances on thirteen-year-old Vivian. It’s unknown how far he went. Immediately after the incident, Vivian’s jealous mother sent her back to school.

The Hartleys only had the illusion of wealth. The unsustainable paradise of Vivian’s early childhood, spent on a gorgeous sun-drenched estate with her beloved Ayah, dwindled along with her family’s’ finances during the 1920s. When she came of age, they could not afford to launch her into society or give her a coming-out party.

Instead, eighteen-year-old Vivian lived in the English countryside, sharing a cottage with her now middle-aged father and whatever woman who would have him. Meanwhile, Gertrude lived in France, still with the same boyfriend who had openly leered at her beautiful teenage daughter.

Vivian and Gertrude (1922)

Gertrude at an event honoring Vivien’s legacy (1970)

Vivian and Leigh

“All of her life, Vivien subconsciously heard the critical voice of Gertrude and tried to be picture-perfect. It was never enough. Gertrude wanted her child’s mind to be as impressive as her beauty and would play Kim’s Game with her, a memory exercise used by British Intelligence and the military. At bedtime, Gertrude arranged objects in a pattern on a tray, then removed them, and had Vivien recreate the pattern in the morning.

All through the night, her little brain ticked over with images of the pattern, a snapshot that became a photographic memory, but it did nothing to control her impulses.”

– Lyndsy Spence, page 49 of ‘Where Madness Lies’

Herbert Leigh Holman was no bore, even if he was a barrister with a strong moral compass. The youngest of six siblings, his family was full of progressive, independent, and talented people, which made it all the more tragic whenever they died young.

One brother, one sister, his mother – he absorbed the grief of them all and quietly carried it around inside of him. His heart and soul wasn’t in his work, but he did find joy in sailing, gardening, fine art, and antiques. Leigh was also already engaged when Vivian Hartley decided that he was the man she was going to marry.

“That doesn’t matter,” the eighteen-year-old girl declared, “he hasn’t seen me yet.”

One of the more poignant revelations in Spence’s book is the role of Vivien’s first husband as a stabilizing influence, even after their divorce. While the public was captivated by her passionate yet toxic relationship with Laurence Olivier, Spence argues that the true love story of Vivien’s life was with Leigh Holman. Despite their separation, Leigh remained a cheerful constant, providing a safe harbor during her darkest hours. Unlike Larry, who eventually abandoned her, Leigh consistently provided effective emotional support until Vivien’s death at fifty-three.

Leigh was thirty-one and Vivian was nineteen when they got married in 1932. Barely a year later, she gave birth to their only child, Suzanne. Diaries kept during her long recovery indicate the traumatic delivery was compounded with undiagnosed post-partum depression.

Maybe it was helplessness in the face of her baby’s endless crying, or her hatred of body odor and excrement, particularly her own. Whatever nullified Vivian’s maternal instincts, it was bad enough that Gertrude had to step in as the main maternal figure in Suzanne’s life after a succession of nannies.

In the beginning, Mrs. Holman genuinely enjoyed married life with her husband. Leigh taught Vivian how to drive a car and delighted in her mutual passion for books, art, and antiques. When they went on weekend jaunts to the country, he displayed a rugged side that thrilled her. More than anything, Vivian found that Leigh’s appreciation extended well beyond her beauty. When she was on his arm, she was more than just a sparkling ornament.

It pained Leigh, seeing his young wife struggle through her studies at the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art. After an especially embarrassing performance in a production of Saint Joan, he just wished she would give it up altogether. At the very least, it was better than Vivian just waiting for him to come home all day. Even then, he just couldn’t understand why she kept putting herself through this. Acting didn’t come naturally to her, and Vivian was already so good at everything else.

In 1937, Leigh’s kind nature was put to the test the day Vivian (now Vivien, as requested by the men who managed her growing career) gently asked him for a divorce. A cruel joke, he initially thought, or maybe some dialogue from a script.

He knew about the affair with that actor. More than once, Leigh made awkward small talk with that actor’s wife. He never thought that the charade would actually collapse, or that Vivien would relinquish parental rights to Suzanne. The day she moved out, leaving only a letter for him and a dressing gown on a hook behind their bedroom door, it finally sank in.

Leigh destroyed the letter but kept her dressing gown right where she left it. If Vivian ever wanted to come home, he told himself, it would be waiting for her.

In 1940, the day his divorce was finalized, Leigh left the courthouse and came home to rubble. The Germans just kicked off the Blitz, assaulting London through a series of systematic bombing raids. First his wife, and now their home.

Herbert Leigh Holman was not a man who forgot his responsibilities. He was suddenly a single father, a concept that barely existed back then, and a divorced Catholic one at that. His seven-year-old daughter had also suddenly lost the only home she had ever known.

He felt every bit of the hurt his little girl felt in the wake of these adult affairs. No matter what else life threw at him – more loss, more bombs, more heartbreak – he would ensure that Suzanne made it to adulthood in one piece.

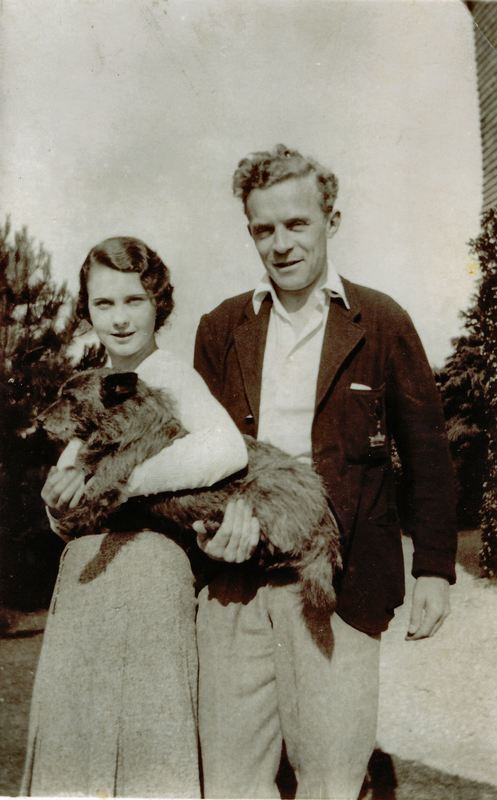

Vivian Hartley becomes Vivian Holman (1932)

Vivian Holman and her daughter Suzanne (1935)

Larry and Vivien

“I never saw such a transformation in a man as the one Larry Olivier went through after he became involved with Vivien Leigh. His entire personality changed. He went from a rather somber, pessimistic chap to an upbeat, gay bon vivant and raconteur. With his close friends, I suppose he had been always like that. With people he didn’t know well, he was usually aloof and humorless.

Suddenly, he was gregarious with everyone. Not exactly backslapping, but expressive and talkative and full of quips. No one knew, of course, that he was so deeply caught up with Vivien, so we all wondered what had happened. Well, she got Larry under her spell, obviously.”

– Laurence Olivier’s friend and fellow actor

Even though he considered him a bore, Laurence Olivier liked Leigh Holman well enough. Honestly, the only problem Larry had with Leigh was that he was married to Vivien. Other than that, he was a perfectly decent chap.

The son of a fire and brimstone man, Larry grew up in a strict middle-class family. His mother died when he was twelve – gentle and God-fearing, she had been his emotional anchor. Her death left him adrift. He carried the weight of her absence throughout his life, fueling his drive and pushing him toward the stage in search of validation and escape. Fear of his father and the pain of that early loss shaped much of Larry’s complex character.

Larry eventually rebelled against the quiet life his family envisioned for him. At the age of fourteen, he attended the Central School of Speech and Drama in London, where he began to hone his acting skills. His early career was marked by amateur theatre performances, but he first gained widespread recognition in 1930 when he joined the renowned Old Vic Theatre.

His first marriage to actress Jill Esmond helped launch his career further. However, their union was troubled by fundamental incompatibilities. Not only was Jill a lesbian, Larry’s seething jealousy of his wife’s successful career as a film star ate at him more than he liked. Despite mutual affection, the marriage suffered – Jill’s subsequent pregnancy with their only child did not improve their strained and sexless dynamic.

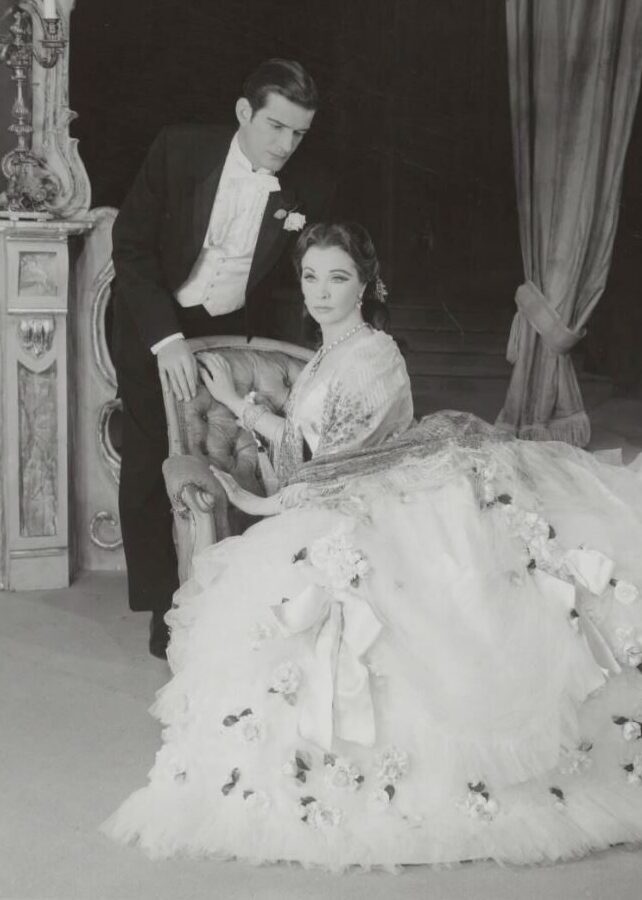

Larry met Vivien in 1936 after a matinee of Romeo and Juliet at the Old Vic. He was Romeo, with Peggy Ashcroft as his Juliet. A rising star too, Vivien had just earned overnight fame inThe Mask of Virtue, a West End play where her angelic looks made up for her unintentionally comedic acting and thin voice.

Per this waif, with her too-long neck and hungry blue eyes, the reason she came to Larry’s dressing room was to invite him to an upcoming party. Some mutual friends from the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art were going. It would be such fun, getting to know each other.

Haunted by the dead bedroom she shared with Leigh and entranced by Larry’s sensuality, Vivien Holman was determined to make this beautiful man her second husband. Before darting out of the dressing room, she gently kissed his bare shoulder. Light-headed from the perfume Vivien left in her wake, Larry knew he had to see this gorgeous girl again. That single soft kiss paved the way for their all-consuming affair. It wasn’t long before it became a well-known open secret, condemned in the eyes of the Catholic Church and barely tolerated by Leigh and Jill.

They stole moments in dressing rooms and in the corners of film sets. Their chemistry was undeniable, and when they were together, nothing else mattered. Not their marriages, not the scandal, or even the Germans. The former Catholic schoolgirl, whose dark curls were cut and glued to the Christ Child’s statue in Roehampton, went skinny dipping with her lover. A virgin when he married Jill, Larry could count the number of times he had sex with his wife on one hand. Yet here he was, being absolutely ravished by this little vixen – sometimes multiple times a day. She worshipped him and he adored her.

Besides the non-stop sex, which Larry sometimes complained about to his friends, it was his Vivling’s sweet little wit and steel trap of a mind that he loved. His love for this woman – the most beautiful woman he had ever seen in his entire life – was almost equal to the shame he felt in his soul. With the grave sin he was committing against his wife and newborn son, much less God, the furies would claim their pound of flesh eventually. It was just a matter of when.

In 1940, after years of subterfuge, Vivien’s grueling ordeal on the set of Gone with the Wind, and multiple letters exchanged with their estranged spouses, came liberation day. With their divorces finalized, Larry and Vivien were finally free. Shortly after, they married in a small ceremony in California.There was a press conference afterwards.

Katharine Hepburn was Vivien’s maid of honor. Larry and Vivien had a screaming match in the car on the way to the wedding chapel. He was thirty-three, she was twenty-six.

Their pre-wedding fight was not the first time that Larry had seen the other Vivien. He first caught a glimpse of her in 1938,when Vivien played Ophelia to his Hamlet.

His Vivien, who always knew the script by heart and delivered it as immaculately as her soft voice allowed, started screaming at him out of nowhere. Even though they were due to go onstage within mere minutes, Vivien’s meltdown behind the curtain briefly stopped the entire cast and crew in their tracks.

The nightmare creature in front of Larry was nothing like his Vivien. It had her heart-shaped face, swan neck, and lovely bottom, but her blue eyes were black with hatred. Her rage ended as quickly as it started – what followed was worse. All sound and fury melted away to unsettling silence. Vivien now stared blankly into the air, her face slack. A chill ran down his spine as he looked into her empty eyes. This close up, clear as day, he saw his Vivien struggling with something behind them.

The other Vivien staggered away from him and stumbled towards the dressing rooms. As Larry stood frozen with horror, cast and crew hurried back to their respective roles, their eyes averted. Five minutes later, his Vivien opened her dressing room door and smoothly sailed onto the stage. She was perfect as always in her performance and deeply apologetic afterwards.

Later that same night, Larry questioned Vivien’s parents about the possibility of mental illness in their family tree. Their evasive non-answers told him everything he needed to know. He had faith that if there was anyone who could push through these whiplash moods, it was his Vivien. When she set her mind to something, she accomplished it.

The trouble was, the mind charting Vivien’s future could suddenly veer off course, shifting from quiet resolve into hostile terrain. This shift was always beyond her control, but it preyed upon her, attacking at her most vulnerable. It feasted on her mind whenever she was being worked to the bone on a job, be it a film set or stage play. When she was forced into physician-prescribed bedrest after yet another flare-up of the tuberculosis patch on her lung. It whispered insidious suggestions in her skull, asking why her husband refused to cast her as his Ophelia in his directorial debut, yet cast her nineteen-year old-clone.Vivien being a thirty-five old Ophelia wasn’t any sillier than Larry being a forty-one year old Hamlet. Maybe he was fucking her.

A shift, resentment, maybe a few drinks, and voilà. From this recipe for disaster, her shadow self, in the flesh.

Despite this, the first few years of married life with Vivien was a dream.

Their beautiful home was always filled with famous faces, high society, and notorious intellectuals. A weekend at Notley Abbey came with a wealth of dirty jokes, late-night conversation, free-flowing fine wine, and occasional bouts of square-dancing. Many a cigarette rested between Vivien’s fingers as she played hostess, a strong drink clutched in her other hand.

Per tradition, everyone stayed over to sleep it off. Guest rooms were always well-stocked with thoughtful touches, courtesy of Vivien. A few books by their favorite author, prettily stacked on their bedside table, or a lovely vase cradling a bouquet of roses, freshly cut from her garden. Even their favorite brand of tea biscuit on their breakfast tray, cozily served in bed.

When the Oliviers first got married, they had only $17 between them, a nadir entirely of their own making. A self-produced American tour of Romeo and Juliet was a genius idea in theory. Who wouldn’t want see Heathcliff and Scarlett, newly married and suddenly famous, make love to each other on stage? In execution, it was a flop that devoured their savings and cost them the respect of American theatre critics. Climbing out of that hole together was anything but easy. By 1945, they were renowned, relatively rich, and expecting a baby.

A baby was the one thing they wanted more than anything. After her first difficult pregnancy with Suzanne, Vivien struggled to conceive. Being plagued by chronic tuberculosis didn’t help either. When she finally got pregnant, it brought the young couple closer together – another dream realized.

That dream died on the set of Caesar and Cleopatra.

Refused a stunt double, a pregnant Vivien had to film endless takes of a single scene – Cleopatra rushes up to her newly earned throne, throwing her arms up in the air to declare, “I am the Queen of the Nile.” After slipping on the sets’ marble floor during a take, Vivien miscarried – the first of three throughout her life.

After losing her baby, Viviens’ shifts in mood became more violent, more vile. Her usual cheeky vulgarity could suddenly curdle into pure venom. Sometimes she was suffocatingly clingy, other times cruelly detached. When she didn’t hate you, she loved you. In Larry’s case, she worshipped him until she thought that he was fucking somebody else.

Vivien’s second husband found himself drowning alongside her. Larry tried to comfort Vivien, to remind her of the love they still had, but his wonderful wife was gradually disappearing. The golden days of their marriage grew shorter, interrupted by long nights of sleepless despair.

Vivien Leigh (1936)

Vivien Leigh (1945)

God and The Angel

“Throughout her possession by that uncannily evil monster, manic depression, with its deadly ever-tightening spirals, she retained her own individual canniness–an ability to disguise her true mental condition from almost all except me.”

– An excerpt from Laurence Olivier’s autobiography ‘Confessions of an Actor’

On the surface, the Oliviers had it all.

Beauty, obviously. Glamour, dripping with it. Rich, of course. Lady Olivier wore the world’s most expensive perfume and Sir Laurence was pouring all of his money into one stage production after another, each one more successful than the last. The Old Vic Company, their loyal acting troupe and coterie, called them God and The Angel. Oh, and the parties they held. Rubbing elbows with all the A-listers over excellent wine in their beautiful home, a large stone abbey once owned by Henry V. Lady Olivier had a painting gifted to her by Winston Churchill, Sir Laurence was knighted by the Queen. On the cover of LIFE Magazine, Lady Olivier’s face glowed with admiration as it was eclipsed by Sir Laurence’s handsome profile.

Behind closed doors, Larry complained about his schizophrenic manic-depressive maniac wife to his girlfriend of the moment. Vivien was getting worse.

She picked fights over nothing, going into hysterics over his friend Kenneth Tynan’s review of their latest stage production and how she was the weakest link in the cast. She accused them of conspiring against her, only to turn around and weep over her lack of faith in him. Sympathetic at first, Larry now resented the disruption, the instability, her apologies – most of all, the lack of sleep. A man needed his sleep, even if he was a god.

He sought solace elsewhere. At first, he made an effort to spare her feelings. He shouldn’t have bothered, his witchy wife knew from the very first mistress. She had a sinister knack for sniffing out the truth, that one.

Each betrayal pushed Vivien further into paranoia. The Oliviers’ passion, mutual respect, affection, shared sense of humor, friendship – everything that made up their fire-bond decayed into a vicious cycle of cruelty and half-hearted reconciliations. The endless cycle’s final step was when yet another seed of resentment took root post-reconciliation.

In 1948, they embarked on a six-month tour of Australia and New Zealand with the Old Vic troupe, performing Shakespeare for sold-out crowds. The Australian press captured theatrical royalty, an adorable king and queen who shook hands and cuddled koalas with elegant ease.

If only they had captured certain scenes that were for the Old Vic troupe’s eyes only. Larry and Vivien hissing ‘fuck you’ at each other before performing a love scene was just par for the course backstage. Larry roughly backhanding Vivien after a meltdown over not being able to find her costume’s shoes, minutes before going out to play a light-hearted comedic scene. Vivien slapping Larry after shrugging off the backhand.

What was meant to be a triumph turned into a nightmare. The relentless schedule, sweltering heat, and Larry’s ever-present frustration with Vivien’s erratic behavior made every performance an exercise in endurance. She flirted with younger men to provoke him, he belittled her performances in return, and the cycle continued.

When they returned to London in 1949, something between them had shifted. One morning, over breakfast, Vivien turned to Larry and told him she no longer loved him. It was not a moment of rage or theatrics. Just a simple fact delivered with chilling finality. Yet, despite her words, she still refused to let go of the marriage, just as Larry, despite his affairs, refused to leave.

Their fights grew uglier, the violence escalating. One night, in a moment of uncontrollable rage, Larry nearly killed her. The next day, Vivien appeared in public wearing an eyepatch to cover the damage. When the press asked about it, she brushed off their concerns, claiming it was to cover a nasty mosquito bite. No one questioned her further, and the world accepted the story without suspicion. The glittering golden couple façade remained intact as their miserable marriage continued.

There had been a few spots of hope. Three, even.

When Vivien brought him A Streetcar Named Desire, desperate to have him direct her in a London stage production, Larry had no idea how much he would come to resent that ghastly play. Yet, for a time, a play about a broken woman provided them a solid foundation to stand on.

He had hoped the role of Blanche Dubois would exorcise the darkness that plagued his Vivling. God knows, she would have crawled over broken glass if it would have helped her performance. Mercifully, it never came to that. All it took was Vivien’s blood, sweat, and tears to manifest the very real creature that stood onstage night after night, unsure and trembling. That creature even earned her another Academy Award in the American film version of Streetcar. In return, it overstayed its’ welcome, whispering lewd suggestions into Vivien’s ear, some of which his wife obeyed without question.

Macbeth, or rather, the cancelled film version of it. With Vivien as his Lady onstage, it was almost like playing Romeo and Juliet again, just fueled by lusty ambition instead of youthful passion. Tynan wasn’t even snarky about Vivien’s performance in that one. If anything, his blood probably ran a little colder than usual during Lady Macbeth’s sleepwalking scene. In ’58, a famous producer committed to financially backing a film version of the play starring Larry and Vivien. When he died later that year in a plane crash, so did the film.

Then there was the baby in ’55, during that godawful production with that poor beautiful pain in the ass Monroe.

Vivien was doing relatively well at the time. She even had a job, a frothy new role in a play, written by her good friend Noel Coward. Her being pregnant at forty-two seemed like the least of her problems. He tried, so wanted to believe that little Catherine would bring his Vivien back to him.

A mistake, giving it a name. Three times now this, yet they always forgot that such hopeful arrogance was a beacon to the unforgiving furies. Yet another pound of flesh, just one of many messily harvested over the years. Afterwards, Larry knew there was nothing left to give for next time. He was all bones now, held together by bits of gristle.

By 1960, Larry had all but abandoned their marriage. He still played the devoted husband when necessary. Vivien, trapped in a mind that betrayed her more each day, clung to the idea of them, convinced they could still find their way back to each other. He was fifty-three, she was forty-six.

Their marriage, once a love story for the ages, had become ashes in their mouths. Divorce was inevitable, a mere formality.

Larry and Vivien in 21 Days Together (1940)

The Oliviers at the St. James Theatre (1957)

Alone with Jack

“My Darling – why I have written My 19th on this little present I don’t know – but as I love you every day of the year. I hope very much that you will like it – use it – and not lose it. It is to thank you for your kindness and goodness to me. It is to tell you that I love you – my beloved.”

– A letter from Vivien to Jack Merivale in 1962, accompanying a gift she sent him

Jack Merivale first met Vivien in 1937. He was friendly with Larry and acted alongside him a few times, but it didn’t stop him from falling in love with Vivien at first sight. Jack, still early in his career, admired her from a distance, but never imagined their paths would cross in any meaningful way beyond work.

Their relationship did not develop immediately, but as Vivien’s marriage to Laurence Olivier began to unravel, Jack became a steady figure in her life. Unlike the relationship she had with Larry, her bond with Jack was less about romance and more about pragmatism. He was not a great actor like Olivier, nor did he share her intense passion for the stage. What Jack offered, especially in her later years, was something far more practical – stability.

Though Jack had long admired Vivien, he never tried to compete with Olivier for her affection. When Vivien’s marriage ended, Jack did not step in as a romantic savior but rather as a constant presence in her world. Jack didn’t shy away from the reality of Vivien’s ‘bad behavior’. He simply accepted the role that needed to be played.

As Vivien’s mental health worsened, so did the strain on their dynamic. Her bipolar disorder became more difficult to manage, and during manic episodes, her behavior could be utterly exhausting. She would sometimes provoke Jack, baiting him into emotional chaos, almost as though she were trying to draw him into a confrontation. Jack rarely took the bait. Instead, he remained unflappable and detached from the storm of emotion she stirred.

Still, their relationship was not without tension. At times, Vivien would find Jack’s detached approach frustrating, even controlling. His emotional distance and his tendency to take charge of her day-to-day care, managing her medication, and watching her like a hawk at social events, could feel like a constraint rather than support. For someone like Vivien, Jack’s unchanging practicality could seem like an imposition, even if it was what she needed most.

By the early 1960s, Vivien’s mental and physical health had deteriorated significantly. Her bipolar disorder had become even more pronounced, and the tuberculosis she had fought off earlier in her life made a return. Jack remained in the role of caregiver, not indulging her emotional demands, but instead functioning more as an assistant to her daily life, ensuring her well-being as best he could under the circumstances.

When Vivien passed away in 1967, it was Jack who found her. Shocked and grief-stricken, Jack immediately called Larry. Despite the fact that he took the call from a hospital bed, his body riddled with cancer, Larry immediately checked himself out and rushed to Vivien’s apartment. He sat with her body for six hours, praying for forgiveness of all the evils that had sprung up between them.

After she died, Sir Laurence Olivier would mourn the loss of two lives – the one he shared with her and one he could have had with his Vivien. He also completely lost his fear of death. By then, so many of his friends and family were already up in Heaven. With Vivling joining the flock, she was sure to be on her best behavior.

Vivien and Jack in Camille (1961)

Vivien, Jack, and their cat Poo Jones (1967)

The Legacy of Vivien Leigh

“Vivien, with deep sadness in her heart and for one fleeting moment tears in her eyes, behaved gaily and charmingly and never for one instant allowed her unhappiness to spill over. This quite remarkable exhibition of good manners touched me very much.

I have always been fond of her in spite of her former exigence and frequent tiresomeness but last night my fondness was fortified by profound admiration and respect for her strength of character. There is always hope for people with that amount of courage and consideration for others.”

– Noel Coward

After Vivien’s 1953 breakdown, Noel Coward, one of her closest friends and collaborators, told Laurence Olivier, “I think Vivien is a spoiled woman a bit bored with things who is making a cracking ass of herself to get attention, and she’d be best served to pull up her bootstraps. We all have our demons, darling.” He then told his friend’s husband that if Larry “had turned sharply on Vivien years ago and given her a good clip in the chops, he would have been spared a mint of trouble.”

Being a playwright, you’d think that Coward would have more insight into the human condition than his callous comments suggest. Sadly, this perspective was commonplace when it to mental illness, even by the most sympathetic of friends. If Coward didn’t consider his words callous, the fact is that they’re objectively untrue.

Leigh Holman never raised his hand once to Vivien in their life together, before and after their divorce. Calm and patient, he provided an environment where Vivien could be more herself. Whenever she grappled with the other Vivien, desperate to keep her contained, Leigh became someone she could lean on, someone who accepted her for all her complexities. There was no jealousy or competition between them, and certainly no Kenneth Tynan and his poison pen.

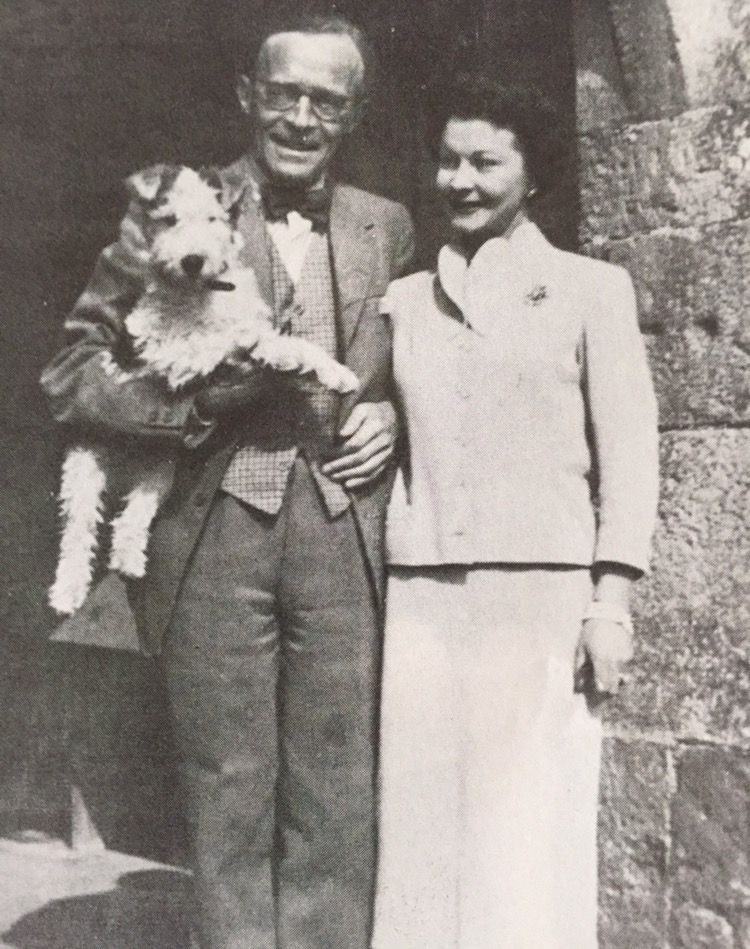

After her divorce from Larry, Vivien started spending more time at Leigh’s farm house in the countryside. At first, it was primarily for Suzanne’s sake. Then, it was every holiday, every summer, long stretches in between, even if Suzanne wasn’t there. While Jack provided stability, it was Leigh’s warmth that helped solidify the structure that kept Vivien’s reality together.

The effect was tangible on her mood swings – there was never any ‘bad behavior’ during these trips to the countryside. They fully enjoyed each other’s company, walking arm in arm through town or pastures, usually with a dog or cat in tow. On Leigh’s arm, she felt like his Vivian – the girl who didn’t even know who Laurence Olivier was, or what it felt like to lose his child.

Leigh’s influence didn’t just change Vivien for the better. Their daughter was raised in a home where love, stability, and emotional care took precedence. Ahead of his time when it came to excellent co-parenting, Leigh was the bridge that helped mother and daughter reconnect as Suzanne grew into a lovely young woman – one that didn’t resemble her mother at all.

Vivien’s presence in Suzanne’s childhood was more akin to a fun older sister rather than a mother. Once Suzanne began having her own children, Vivien did her best to be a good grandmother. Even if she was surprised to find out that toddlers wouldn’t enjoy a nice salad for lunch, she enjoyed reading Peter Rabbit with them and became the official narrator of the audiobooks. Even in death, her grandchildren could still find comfort in her reading them a story.

Suzanne’s long, healthy, happy life marked the end of a generational struggle, free from the pain that stole so much from her mother’s short life. Vivien’s journey, with all of its despair and sleepless nights, ultimately helped change her family tree for the better. For a woman whose life was ruled by unending cycles, she and Leigh did manage to break one.

Leigh and Vivian with a dog (1932)

Leigh and Vivien with a dog (1965)

Why Should You Read This?

“O, that way madness lies; let me shun that; No more of that. It is in the midst of the lament that Lear suddenly changes gears: “O, that way madness lies; let me shun that; no more of that.”

– ‘King Lear’ by William Shakespeare

None of us are safe from forces out of our control, no matter how powerful, rich, brilliant, or beautiful.

You may be the richest man on the Titanic, but you die clinging to a raft, your frozen body found ten days later. You may have the legacy of being two of the best cast members Saturday Night Live ever had, but one of you will be murdered (by your own wife, no less) and the other dies on the floor, begging the sex worker stealing their watch to please stay. You may be a genius, but you’re off-meds and can’t stop tweeting about Hitler.

The best celebrity biographies strip away layers of fame and glamour of an icon, exposing the conflicted and usually traumatized person underneath. They show how personal struggles can destroy a dream that came true, serving as contemporary fables that usually double as cautionary tales.

Let’s be honest. More likely than not, you have known or met someone like Vivien Leigh. If you know them well, you probably have a front row seat to the trials they’ve endured. If you met them when they were at their worst, it was probably a deeply unpleasant experience, one you’d never want to repeat if you manage to walk away whole.

Mental illness can manifest in countless challenging ways. It might appear as relentless anxiety disguised as controlling behavior, deep depression that isolates the sufferer from support, or bipolar disorder causing unpredictable mood swings that take their toll over time. It can surface as obsessive tendencies mistaken for stubbornness or paranoia interpreted as mistrust. These aren’t character flaws; they’re symptoms. By recognizing this, we validate medical conditions more painful than any broken bone and provide tangible hope to those fighting battles we cannot see.

In Where Madness Lies, Lyndsy Spence never sugarcoats her prose. She only reveals with surgical precision.

As she navigates us through Vivien’s complex emotional landscape, Spence balances extensive research with narrative flair. Her ability to blend scholarly expertise with engaging writing forms the emotional backbone of the book. She carefully captures the era’s troubling attitudes and barbaric treatments, underscoring Vivien’s profound isolation in her battle. The narrative extends its reach beyond the individual experience, offering awareness not only to those grappling with mental illness but to caregivers, whose tireless efforts are usually awarded with more pain.

Unlike previous Vivien Leigh biographies, Spence explores her subject’s early traumas in intimate detail, vividly connecting them to her later struggles. The abuse, abandonment, and emotional neglect of her childhood are presented openly, explaining her unstable relationships and hypersexual behavior during manic episodes. This context makes Vivien’s sudden shifts from poised elegance to chaos all the more understandable. Most of the damage she inflicts is almost like she’s punishing herself, eroding everything she holds dear – particularly her second marriage.

The book’s strength lies in its balance between tenderness and stark honesty, which is crucial to Spence’s choice to not censor Vivien’s disease and the damage it inflicts throughout the book. The opening chapter alone is a harrowing read with the cinematic slow burn of a horror movie.

In peaceful moments, Spence shows every lovely detail of the ‘good’ Vivien – her warm wit, dogged determination, her charming foul mouth, calculating mind, and gentle nature. Whenever Vivien’s shadow self sinks its hooks into her unwilling flesh, the shift from the ‘good’ Vivien to ‘the other’ is chilling. Spence doesn’t shy away from this dark side, capturing the reality of bipolar disorder in an era that considered it a moral failing and not a medical condition.

Spence also handles both of Vivien’s husbands with great sensitivity. Usually a footnote in other biographies, Leigh Holman quietly emerges as the heart of Where Madness Lies. Even though Leigh is constantly tested by tragedy throughout his life, his wholesome devotion to family always overcame anything that threatened to break him. Sir Laurence Olivier, with all of his transgressions against Vivien, is depicted with nuance. Spence holds Olivier accountable for his actions against his sick wife, but she also shows how his struggles in caring for Vivien’s complex emotional needs influenced his decisions.

Completely devoid of hollow idolatry, Where Madness Lies feels refreshingly urgent. It’s the story of how a neglected child became a remarkable woman, fighting tooth and nail with her dark twin every step of the way. Potential readers include those interested in the history and stigma surrounding mental health, lovers of Hollywood’s golden age, and anyone attempting to break a cycle of their own.

Vivien in The Mask of Virtue (1935)

Lady Olivier in Macbeth (1955)