Lyndsy Spence on Vivien Leigh, Bipolar Disorder, Uncensored Reality, and Why Everyone Needs a Leigh Holman in Their Life

Lyndsy Spence specializes in women who defy easy categorization. In her latest biography, Where Madness Lies: The Double Life of Vivien Leigh, she turns her attention to one of Hollywood’s most enigmatic figures and the endless vicious cycle that ultimately unraveled an extraordinary life.

Spence’s connection to Vivien is lifelong. As a child, she learned of a distant family connection, and after watching Gone with the Wind, she was captivated by Vivien’s screen presence and talent. After writing multiple books about other famous ‘difficult’ women, it was time to tell Vivien’s story.

Shucking the confines of conventional biography, Spence uses the last thirteen years of Vivien Leigh’s life to frame the narrative. The book opens with Vivien in the middle of a nervous breakdown, unfolding the harrowing episode like a slow-burn horror film. Spence strips away layers of Vivien’s glittering public persona with surgical precision, revealing the beauty and brutality that shaped the struggling woman within.

I spoke with Spence about what it takes to get to the heart of her subjects, writing about the ugly reality of mental illness with respect, and why Vivien Leigh remains relevant in an era increasingly skeptical of stardom.

Lyndsy Spence specializes in women who defy easy categorization. In her latest biography, Where Madness Lies: The Double Life of Vivien Leigh, she turns her attention to one of Hollywood’s most enigmatic figures and the endless vicious cycle that ultimately unraveled an extraordinary life.

Spence’s connection to Vivien is lifelong. As a child, she learned of a distant family connection, and after watching Gone with the Wind, she was captivated by Vivien’s screen presence and talent. After writing multiple books about other famous ‘difficult’ women, it was time to tell Vivien’s story.

Shucking the confines of conventional biography, Spence uses the last thirteen years of Vivien Leigh’s life to frame the narrative. The book opens with Vivien in the middle of a nervous breakdown, unfolding the harrowing episode like a slow-burn horror film. Spence strips away layers of Vivien’s glittering public persona with surgical precision, revealing the beauty and brutality that shaped the struggling woman within.

I spoke with Spence about what it takes to get to the heart of her subjects, writing about the ugly reality of mental illness with respect, and why Vivien Leigh remains relevant in an era increasingly skeptical of stardom.

Who are you and what’s the background of ‘Where Madness Lies’?

I’m Lyndsy Spence – biographer and historian, a little bit of a screenwriter sometimes. I’ve loved Vivien Leigh since I was a child. She was related to my Irish great grandfather, so I’ve always known of her as a spectre in the family. I think my proper love affair started when I watched ‘Gone with the Wind’. After seeing that, I was just completely under her spell. I started to watch everything I could, read everything I could. I even tried to copy her look as a young kid. You know, the hair parted in the middle, and the little Scarlett smile.

When I was about 17, I wrote a screenplay based on her life. I can remember working frantically on it and sharing it with my friends on MSN Messenger. I ended up getting a literary agent due to it. I got to go to London, got to meet loads of really cool people – then the film adaptation of the screenplay went into development hell. I then transitioned into writing books, particularly about famous scandalous women. Still, in the back of my mind, I never let go of Vivien’s story.

Years later, after publishing my book on Maria Callas and response I received per that, my commissioning editor encouraged me to tackle Vivien Leigh’s biography. I resisted at first, but then I went off secretly and wrote the first six chapters. I wrote it as fiction at first – I changed everyone’s names, so it wasn’t Vivien, Larry, and the like. In a way, I wanted to break out of my comfort zone by not doing a traditional biography, which instinctively felt like the right way to tell her story. In the end, I went back to my editor and said, you know, I’ve got these six chapters – would you like to read them?

With celebrity culture dying and only a handful of films to her credit, why should we give a damn about Vivien Leigh in 2025?

I think Vivien is sort of a predecessor to a lot of things happening today. I think of somebody like Taylor Swift, re-recording her masters. Somebody tried to take her authority away from her art, and she said, ‘well, no, you won’t do that. I’m going to do this instead and back stronger for it.’ Or Pamela Anderson, who got sick of being typecast and did the outrageous thing of simply not wearing makeup, taking back complete control of her image. Vivien was doing this in the 1940s and 50s. Hollywood wanted to mold her into a ‘film star’, and she said, “I’m not a film star. I’m not playing the studio game. You can’t market me.”

That’s where she’s quite different from icons like Marilyn or Audrey or Elvis – Vivien never set herself up as a product. As a fan, I kind of wish she had because we would have had more films, but she stayed true to her vision for her art and career. Sure, sometimes she did the big-budget stuff because she had bills to pay like everyone else, but usually she followed her heart, and what spoke to her as an artist.

Then, in the late 1950s and 60s, Vivien started to open up about her mental health and her nervous breakdown in 1953, which was taboo back then. Although she seemed quite supernatural on screen, if you read the few interviews she gave in her lifetime, you really see the humanity behind the art. I think that speaks to people because film stars are often held up as idols we can’t compare to, especially today, with airbrushing and filters making people feel inadequate. To have an enigma like Vivien Leigh come out and say, “I’m struggling, I had to go to hospital, I’m on medication” – I think that spoke to a lot of women at the time, who didn’t have much of a voice or authority in society without fighting for it. I think that’s what makes her so different, and why she’s still relevant today.

Instead of a ‘cradle to grave’ narrative, your book focuses on the last thirteen years of Vivien’s life. The first chapter takes place in 1953 and gives us a close-up of Vivien at her worst during a nervous breakdown in India. Did you always intend to open the book with this incident?

Yes, I always wanted to open with it. When I think of my different paragraphs and chapters, it’s almost like a cinema reel. I suppose my mind just works quite cinematically, so I always saw it that way. You know how everyone talks about Vivien’s marriage to Olivier – one minute it’s beautiful, the next it’s not. I thought instead of wading through everything to get there, why don’t we just start in India and show what she really lost in the process of struggling with her bipolar disorder?

I think Vivien was kind of an old soul. You know, when someone you love is terminally ill, they often reach a sort of inner peace even if the people around them haven’t reached it yet. There’s a moment in the book, just before Vivien gets really ill and dies, when she goes back to visit India, and it’s very spiritual for her. Peter Finch, her boyfriend during the 1953 breakdown, looks her up again and tries to pull her back into that chaotic lifestyle, but she’s able to resist him because she’s evolved. By then, she’s made peace with her mother, with the daughter she more or less abandoned, her grandchildren, and there’s just this peacefulness and kindness about her.

I think Vivien instinctively knew her time was coming to an end. Even when she was diagnosed with TB and everyone thought she’d just get over it like the flu, she knew differently. But Vivien being Vivien, she was more concerned about her ex-husband, who was receiving cancer treatment at the time.

It might sound cold, but what I love about Vivien’s death is that she died alone. I love that she had that dignity, that privacy, because most of her struggles were under the microscope. It’s almost animalistic, like a cat, going off into her own environment to die quietly once everyone had left her alone, entirely on her own terms.

Speaking of marriage – you show a lot of empathy for both of Vivien’s husbands, especially her first husband Leigh Holman. Usually relegated to a footnote in previous biographies about his ex-wife, Leigh was a lifelong stabilizing influence for Vivien and their daughter. Did your opinion of him evolve during your research? If so, how?

I just love him so much. I think everybody should have a Leigh Holman and treat him right!

Yeah, it definitely shifted with Leigh. I always thought, well, he must have had a bit of a sparkle if Vivien kept going back to him in a platonic way. I mean, I don’t want to use the phrase “good man,” because nobody’s all good, but he must have had a really good moral compass. And Vivien, behind all the glitz and glamour and misbehaving, must fundamentally have been a good woman.

For me, the real love story is Vivien and Leigh Holman. That’s the true love story, because they feel like soulmates. There’s this beautiful parallel: a picture of them before they married, wearing country clothes and holding a dog, and another similar picture taken just before Vivien died. It’s almost like Peter and Wendy. I think if Vivien hadn’t died at such a young age, she would’ve probably veered back to Leigh. Maybe not romantically, but certainly I could see them living together and settling into that peaceful life he wanted for them at the start. She started spending every Christmas with him, she’d visit his garden, and there’s a lovely photo of Vivien and Olivier’s niece with Leigh, just quietly looking at plants – it’s almost like the life Vivien should have had with Leigh and their child.

I was amazed too by Leigh’s eccentric and accomplished sisters. He clearly respected strong women. His sisters and mother were independent, strong-willed women. So, he recognized Vivien’s strength and achievements. Perhaps because of growing up surrounded by these independent women, Leigh craved domesticity, a quiet life with a wife, which he sadly never fully achieved. It’s quite remarkable to think of him as a single father in the 1930s. That wasn’t the norm at all.

There’s a part in the book that really broke my heart. It parallels Vivien’s divorce from Olivier with her divorce from Leigh. Vivien is in Hollywood, writing to Leigh, “Oh darling, I hope you don’t have too much trouble with this divorce.” But for Leigh, it was his entire life. He went to court alone, returned to the home he once shared with Vivien and their child, and the house was destroyed by a German bomb. He lost everything, and yet he rebuilt. He lost family during the Blitz, he lost a sister young, and his parents and brother in World War I. The fact that despite all this tragedy, he kept choosing kindness really spoke to me. It made me see him in a new light and have so much respect for him.

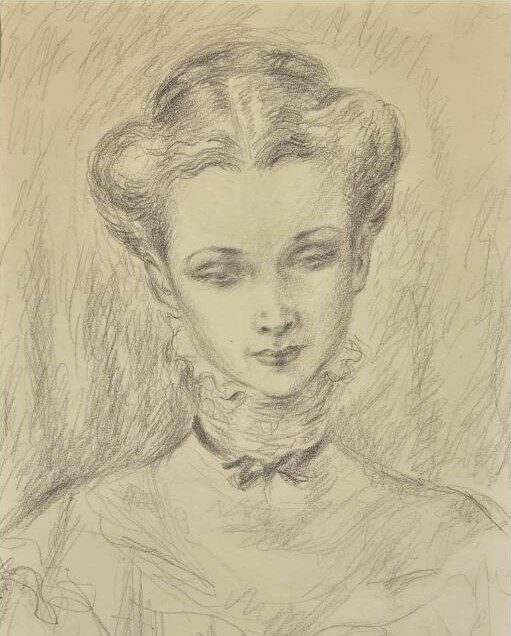

A sketch of Leigh Holman by Hester Holman, his younger sister – four years later, she died in an accident (1930)

Vivien in costume for a stage production of ‘The Doctor’s Dilemma’ – sketch by Roger Furse (1941)